Who’s right about inflation, and who’s wrong? Experts will be debating this question, with no conclusive answers, all the way through the holiday season and into next year. Where it really matters, though, is at the level of central bank deliberations, and here the solid wall of uniformity – it’s all just temporary! – is starting to split. How a central bank views the inflation threat strongly influences how that bank will guide interest rate policy in the months ahead. There are some clearly diverging paths here now.

Hawks, Doves and Warblers

On one side are those who have already put a foot forward – not in actually raising rates but in setting firm expectations. Here you have the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Canada. Call this trio the Commonwealth Hawks. It’s true that the BoE surprised the market last week when it chose not to raise the bank rate (the interest rate it controls, similar to the US Fed funds rate). But in a country where natural gas prices can rise ten percent in a matter of days, the BoE has signaled a clear concern about inflation and is likely to take action in the very near term.

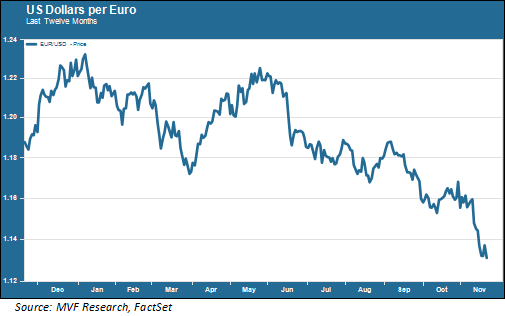

On the other side of the spectrum sits the European Central Bank. Inflation is up in Europe, with the Consumer Price Index posting a 4.1 percent gain in October. But ECB head Christine Lagarde has been forceful in projecting a dovish stance on both interest rates and the bank’s bond-buying program. The ECB doves appear to finally be getting through to both the bond market and to currency traders. The euro has been falling steadily against the US dollar since midsummer, with the pace of the drop quickening in recent days as Lagarde has become the avatar of monetary doves.

Then we have the Fed. The world’s most influential central bank (arguably the world’s most influential institution of any stripe) is somewhere in between the Commonwealth Hawks and the ECB Doves. Call them hooded warblers, perhaps, if we want to stick with the avian taxonomy. According to the All About Birds website (allaboutbirds.org) “hooded warblers sing an emphatic and loud ringing song.” That sounds about right. The Fed’s song for most of the year has been emphatic about the transitory nature of inflation, with a loud ringing repetition that it doesn’t intend to raise rates any time in the foreseeable future. But more recently the loud song appears to be masking some genuine disagreements among Fed members as the monthly inflation numbers keep building the case for something less temporary than seemed to be the case earlier in the year. So the Fed may be singing a sweet song to appease markets, while internally coming to terms with how they might have to change policy if the sticky inflation case continues to build through the end of this year and into the first quarter of next year.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting a Repricing

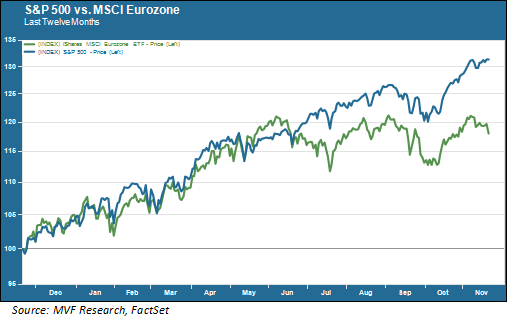

This divergence among central banks is already having an effect on a variety of asset classes, and we may only be in the early stages of some significant repricing. Consider the Lagarde effect, which by affecting how the euro trades against other currencies is also having an effect on European equities. After trading roughly in line with US stocks earlier this year, Eurozone equities have sharply diverged recently.

If market sentiment crystallizes around the notion that the Fed is more likely to gravitate towards the hawk camp (which would be the likely outcome of a stickier inflation environment) then the performance gap between US and European equities could grow wider still. Of course, the currency effect is not the only factor driving the relative performance of equity asset classes, but it is an influential one. The Lagarde effect could cast a long shadow over European equities well into 2022.

But a more hawkish Fed – or at least the perception of a more hawkish Fed – has implications for many other asset classes. Junk bonds are not likely to stay at negative real yields forever. Other frothy corners of the market are vulnerable to a broad-based credit market repricing as well. Of course there will always be counterintuitive surprises. But short duration bonds, high quality domestic equities and a few inflation-resistant alternatives might be a good way to start.