Major macroeconomic indicators come with their own special days of the week. We have “Jobs Friday” for the monthly labor market report put out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and “Inflation Tuesday” when that same institution publishes the Consumer Price Index for the prior month. Those two reports in particular generate lots of furrowed-brow chatter among financial media talking heads when they come out, and rightfully so. There is another day of the week, though, that tends to come and go without creating much fanfare. Productivity Thursday was yesterday – did anyone notice? Our good friends at the BLS are the custodians of this metric as well. According to their release yesterday, labor productivity in the US rose by 1.7 percent in the fourth quarter of last year. That is less than the 2.0 percent rate economists expected, and well below the productivity trends of decades long past – the last time we had a productivity surge in this country was in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when advances in information technology finally showed up in the real economy.

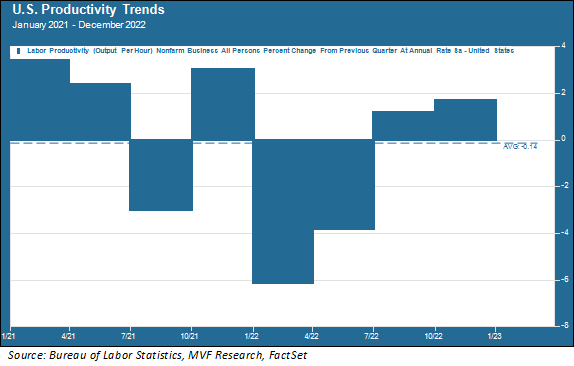

But hey – 1.7 percent is at least better than the minus 0.14 percent average rate from the beginning of 2021 to the present, as shown in the chart below.

What’s So Special About Productivity?

The underlying assumption for any capitalist economy is growth: things in the future will be more prosperous than things today because the rate of economic growth will outpace the rate of population growth (i.e., per-capita wealth, on average, will be higher tomorrow than it is today). Since about the last third of the nineteenth century, barring a small number of sustained downturns (most notably the Great Depression) that assumption has played out. The continuation of this long-term trend relies on two factors: demographics and productivity. Demographics refers to the percentage of the population actively employed in the labor force; a higher percentage of the population engaged in gainful employment means a lower dependency ratio (i.e. more independent souls working, and fewer dependent folk relying on those workers). Productivity is the measure of how much those workers can produce for every hour of labor. The more output per hour of effort expended, the higher the productivity. This is the formula for long-term growth; there is no alternative route to that goal of greater future prosperity.

Trouble On Both Fronts

The problem we face today is that demographic trends are headed in the wrong direction and, so far at least, there are few signs of improved productivity to pick up the slack. The demographic problem is twofold. First, a multi-decade tailwind of benign labor market conditions has effectively ended. This tailwind started in the 1970s with the increased entry of women into the full-time labor market (i.e., increasing the supply of labor relative to demand) and continued in the 1980s and 1990s with China’s entry into the global economy. The second demographic challenge is the dependency ratio we referred to above. Populations around the world are ageing, life expectancies are longer and people are having fewer children (and waiting longer to have them). In the very near future there will be fewer active workers to care for a larger number of older citizens requiring greater care.

The only solution to the demographic challenge is productivity. The good news, potentially, is that it there can be a meaningful lag between the time when a game-changing innovation takes place and when that innovation really kicks into economic activity. We noted earlier that this was the case with the last productivity surge – the technological innovations showing up in the economy’s performance in the late 1990s and early 2000s began in the 1960s with the advent of semiconductors and Moore’s Law. Going back even further in time, from the time electricity was invented in 1879 to the time when 50 percent of US households were switched on, in 1919, was a span of 40 years.

So it may well be that gains from some of the more recent areas of development – we think artificial intelligence and quantum computing may be at the forefront – are just around the corner. If so, they couldn’t come at a better time. Meanwhile, it would be worth one’s while to pay attention to Productivity Thursday, even if (or maybe especially because) nobody’s talking about it on CNBC.