It’s the first Friday of the month, and we all know what that means. Jobs Friday! We know, because lots and lots of words get put to paper describing the latest trends in the labor market (which, by the way, continue to be resoundingly strong, with the lowest unemployment rate since 1969). Jobs, inflation and GDP form a sort of holy trinity of macroeconomic performance measures. They are the ones that get talked about the most and, in the popular mind, are the ones that most comprehensively stand in for the performance of the economy as a whole.

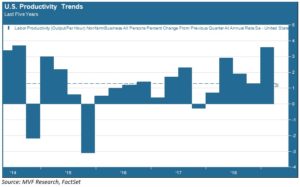

The day before Jobs Friday another performance measure came out, to basically no fanfare whatsoever. First quarter labor productivity increased by 3.6 percent from the previous quarter (on an annualized basis), well above expectations and the largest quarterly increase since 2014. The chart below shows the five year trend in productivity.

Growth For Free

It is a matter of perpetual bemusement for us that nobody – by which we mean the chattering class avatars of financial media outlets – seems to cast an eye in the direction of the quarterly productivity report when it comes out every quarter. It’s strange because we are always talking about growth. Growth is the lifeblood of the economy, and there is no end to the discussion about how to get more of it.

Well, the answer to the question about how to get more growth is actually quite simple. You guessed it…productivity. In the thousands of years of human civilization sustainable economic growth has only come about by three means: (1) an increase in population, (2) an increase in the percentage of those engaged in gainful labor relative to the size of the population as a whole, or (3) an increase in productivity, defined as the ability to produce more goods and services for every hour worked. Productivity is growth for free – you produce more stuff with the same amount of inputs. Businesses can use the productivity windfall in all sorts of ways: retain a higher percentage of profits for future investments, hire more workers to expand the business, or pay out more in shareholder dividends. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Put another way, the only way that our economy will grow over the long term is through increased productivity. In the short term it is possible to grow through fiscal and/or monetary stimulus, but those are limited in duration and come at a cost. So, again, it is always surprising to see how little attention is given to the one single macroeconomic data point that is the most accurate proxy for long term growth.

Still Got a Long Way to Go

So what to make of that 3.6 percent productivity boost we got in the first quarter? Well, it’s a nice change from recent underperformance, but still not much in terms of a broader historical context. The chart below elongates the time period to show productivity trends going back to 1990.

As the above chart shows, productivity growth was far stronger in the economic growth cycle of the late 1990s and early 2000s than it has been in the post-recession cycle from 2009 to the present (ignoring the recovery-from-trough quarters immediately after the recession). Economists differ as to why this is the case, with arguments ranging from secular stagnation (chronically low demand) to the delayed economic impact of recent innovations like artificial intelligence. We probably will not have a definitive answer to this question for some time. What will be interesting to see in the quarters ahead is whether the Q1 outperformance in productivity continues or if it turns out to be an anomalous blip. A surge in productivity would suggest a new phase in the current growth cycle. Whether the economy can replicate the productivity gains of earlier innovation cycles, though, remains to be seen.