Meet the new decade, same as the old decade – only slower, and with even less inflation. That is the picture presented by the Federal Reserve at the conclusion of this week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting, where the Fed meets periodically to discuss and implement monetary policy.

It might seem strange to think that, after all the tumultuous change the world has gone through in the past seven months, the most likely outcome for the US economy is simply more of what it was like before the pandemic. In many ways the Fed’s analysis is in line with our own economic outlook at the beginning of this year, well before the coronavirus arrived on our doorstep. The fundamental barriers to higher structural growth appear to be firmly rooted. These include: the demographics of an ageing population (lower participation rate in the labor force); persistently widening income inequality (lower rates of spending power by a larger swath of the population); the overhang of public and private debt (which has gotten exponentially worse over the course of the virus); and a global economic shift in the balance of power from the developed economies of the West to the rising ones of the East, led by China.

But the numbers only tell part of the story. While the macroeconomic trends may point to a “Groundhog Day” economy where every day is the same, the world of the 2020s will not be the world of the 2010s. Translating economic analysis into investment management requires understanding more than just the headline numbers – indeed, understanding the practical limits of what those numbers tell us.

Gentle Decline by the Numbers

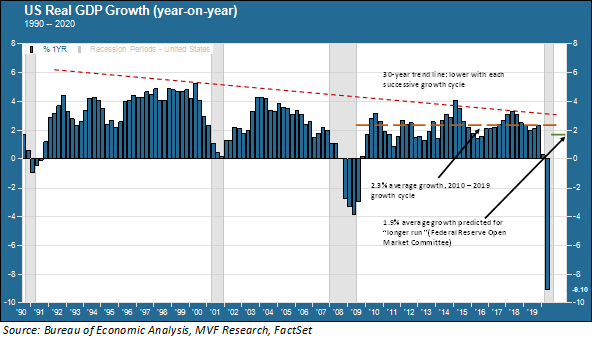

Let’s take at those numbers, though. The chart below shows the year-to-year trend in real US GDP growth for the past 30 years. It encompasses the three growth cycles of the 1990s, the mid-2000s and 2010-2019, punctuated by the recessions of 2001, 2007-09 and 2020.

It is easy to see in the above chart how the pace of growth has moderated from the robust levels of the 1990s growth cycle to the relatively tepid 2.3 percent average rate of the 2010 – 2019 period (which, remember, was the longest economic recovery period on record). You can also see that the “longer run” projections by the FOMC are for growth to moderate further still to 1.9 percent. Take out the pandemic distortions – the dramatic drop in this year’s second quarter and the expected bounce-back that should occur in the year’s remaining quarters — and you are left with the gentle moderation of an ageing economy.

Every Sector is the Tech Sector

It is an economy, however, that is characterized in large part by the rapidly increasing dominance of technology. It’s already misleading to think of “technology” as something bundled up in just one of the eleven major industry sectors in the S&P 500. After all Amazon, to cite one prominent example, is not even in the tech sector. The online retail and cloud computing giant is officially part of the consumer discretionary sector. There it is just one of 60 companies listed on the blue chip index (but accounts for fully half of the sector’s market cap). Alphabet, Facebook and Netflix are also tech giants, but are part of the communications services sector alongside old-world media organizations.

Dig into just about any industry sector in fact — from consumer staples to industrials and beyond — and you will see technology at the center of the most successful business models, often anchored by cloud computing platforms on which the companies run their business operations. These, of course, are provided by the likes of a small number of tech giants led by Amazon, Alphabet and Microsoft and supported by an ecosystem of data warehousers like Snowflake (which barged into the market via an IPO this week that instantly made it three quarters the size of IBM in market cap), retail payment systems like Shopify and hosts of software offerings for predictive analytics, financial technology and everything else that makes up the “techonomy” ecosystem.

New Metrics for an Old Economy

Part of the problem economists face today – including those at the Fed – is that their traditional tools, models and metrics are increasingly out of line with the dynamics of the technology-driven economy we sketched out in the preceding paragraph. The calculation methodologies for headline measures like GDP, inflation and unemployment have not changed much since the aftermath of the Great Depression of the 1930s, when most of them were developed. In other words, we continue to use measurements today whose original purpose was to try and understand a world that existed nearly a hundred years ago – a world that very much no longer exists.

You’re going to be hearing a lot more about this from us in the coming months, because we believe that to understand where the opportunities and risks lie in investment management today is not to rely solely on models and metrics that have outlived their usefulness. What should come in their place? That in part remains to be seen. But it is worth dwelling for a second on the etymology of the word “economy” – which means “household” in the ancient Greek. We study the economy because we are trying to understand the quality of life that people – households – experience in a given time and a given place. We try to come up with useful quantitative ways to describe qualitative values.

The problems we identified above, such as ageing, income inequality and debt, are qualitative problems. A measure like GDP may give us a partial description of the problem but by no means a complete one. Meanwhile there are tens of thousands of companies out there making millions of decisions every day about how to solve some small part of those problems – in a haphazard way the usefulness (or not) of which will only emerge gradually, organically, over time. Our challenge as asset managers – as stewards of the money entrusted to our care – is to somehow make sense of all this often contradictory information and discern the structural developments we believe will be influential in the months and years ahead. It’s not easy – but it is our job and our responsibility to meet the challenge with all the tools at our disposal – old tools and new metrics alike.