We normally do not use this column as a place to focus on the merits, or lack thereof, of a particular investment asset, be that the common shares of a publicly traded company, mutual fund, hedge fund or what have you. But we do focus from time to time on particular strains of human thought that translate into specific investment strategies – growth, contrarian, momentum and all the rest. Our theme today is that particular way of looking at the world that translates into a strategic approach called the “perma-bear,” or one who is perennially positioned for a bear market, year in and year out. In service of that theme we will call out one particular asset – a mutual fund called the Hussman Strategic Growth fund.

The stated investment objective of this fund is “long-term capital appreciation, with added emphasis on the protection of capital during unfavorable market conditions.” How would that have worked for you if you had invested, say, 10 years ago for “long term capital appreciation?” Well, your average annual return over those 10 years, your most recent quarterly statement would have told you, was minus 7.2 percent. Minus 8.8 percent over the last five years. Even over the last twelve months, which includes a near-bear market in fall 2018, your total return was in the red – minus 3.8 percent.1 Such is the experience of one of the market’s best-known perma-bear vehicles.

Reality Bites the Bear

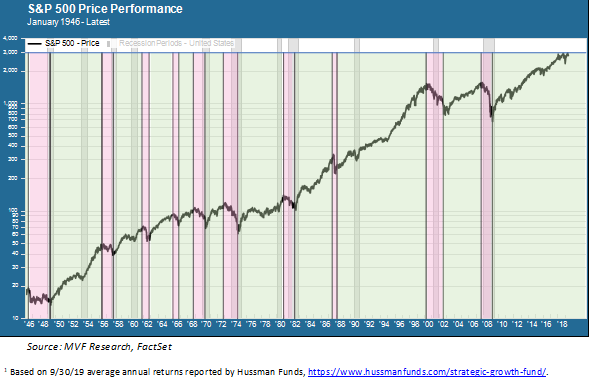

We present this data with no particular animus towards the Hussman fund per se, but rather to underscore the challenge reality presents to anyone who begins each calendar year prepared for the sky to fall. The chart below shows every instance of a bear market in the S&P 500 since 1946, represented by the pink column showing the peak-to-trough duration of each event.

As the chart shows, there were ten specific instances of bear markets – defined as a fall of 20 percent or more from the previous peak – over the roughly three quarters of a century since the end of the Second World War. You can see from the proportions of pink and green shading on the chart that for the vast majority of this time the market has not been in bear country. Now, there certainly have been times when the bear showed up with more frequency, notably the period from about the mid-1960s to the early 1980s. But since the market bottomed out in August 1982 – fully 37 years ago – there have been a total of three bear markets. It is easy to see why a perma-bear strategy has not been a successful long-term approach for this period. The question we find interesting, though, is what keeps anyone in these strategies. The answer, we suspect, lies in the psychological phenomenon of loss aversion – the outsize impact a monetary loss can have on one’s state of mind even if that loss is more than compensated for by monetary gains over time.

The Allure of the Broken Clock

Loss aversion is why investors remember with absolute crisp-clear clarity where they were the day Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, or Black Monday when major stock indexes fell more than 20 percent in a single day. Does anyone remember where they were on some random day in March when the S&P 500 gained two percent, or even how you felt on December 31, 2013 when the S&P 500 posted an annual return of more than 30 percent? No – that’s the asymmetric power of loss aversion. It explains what we sometimes call the “broken clock theory” and we think it also explains why perma-bear strategies like the Hussman fund continue to attract investors despite a sustained track record of underperformance.

A broken clock is right twice a day. It’s wrong for all the other minutes, but for those two minutes, it’s right. Take that analogy out to the market. If you’re a perma-bear, on any given day you will be out there on CNBC or Bloomberg News explaining why the world is about to come crashing down on that day. Most of the time you will be wrong. But on those rare occasions when you proclaim doom and doom ensues – well, you are hailed as a god of finance. In 1987 a Lehman Brothers analyst named Elaine Garzarelli predicted that the market would crash – and it did! Lucky or not, Garzarelli’s star ascended to the brightest heavens of financial punditry. Likewise, Hussman and other perma-bears bathed in the spotlight as the markets fell apart in 2008. Those moments matter, because they register so clearly and distinctly in our brains. Loss aversion. Those two minutes of being correct punch above their weight, never mind the other 1438 minutes of being wrong. This is clearly irrational, because in the end you come out worse when the results of being wrong all those minutes add up. But that’s what behavioral finance is all about – irrationality rules the day, and the perma-bears stay in business.

Now, to not be a perma-bear does not mean that one has to be a Pollyanna, ever optimistic that the sun will shine down on all of creation all the days. There are times to take a more wary view of the evolving state of things, and there are times to be more positive. As we have noted in a number of recent columns, we see many reasons to cast a wary eye on potential developments in the year to come. But to be perpetually pessimistic about market prospects would not, in our opinion, serve the long-term interests of our clients, and we prefer to look to evidentiary data than to fall prey to the loss aversion trap.