It’s been one of the go-to conversation starters of the year – how about those gas prices huh? Prices are higher for all manner of goods and services, but there is a special place in the heart of our petrol-besotted nation for those flashing red signs at the local Shell or Sunoco station, telling us exactly, to a penny, what the price of a gallon of the stuff is today versus what it was a day, a week or a month ago.

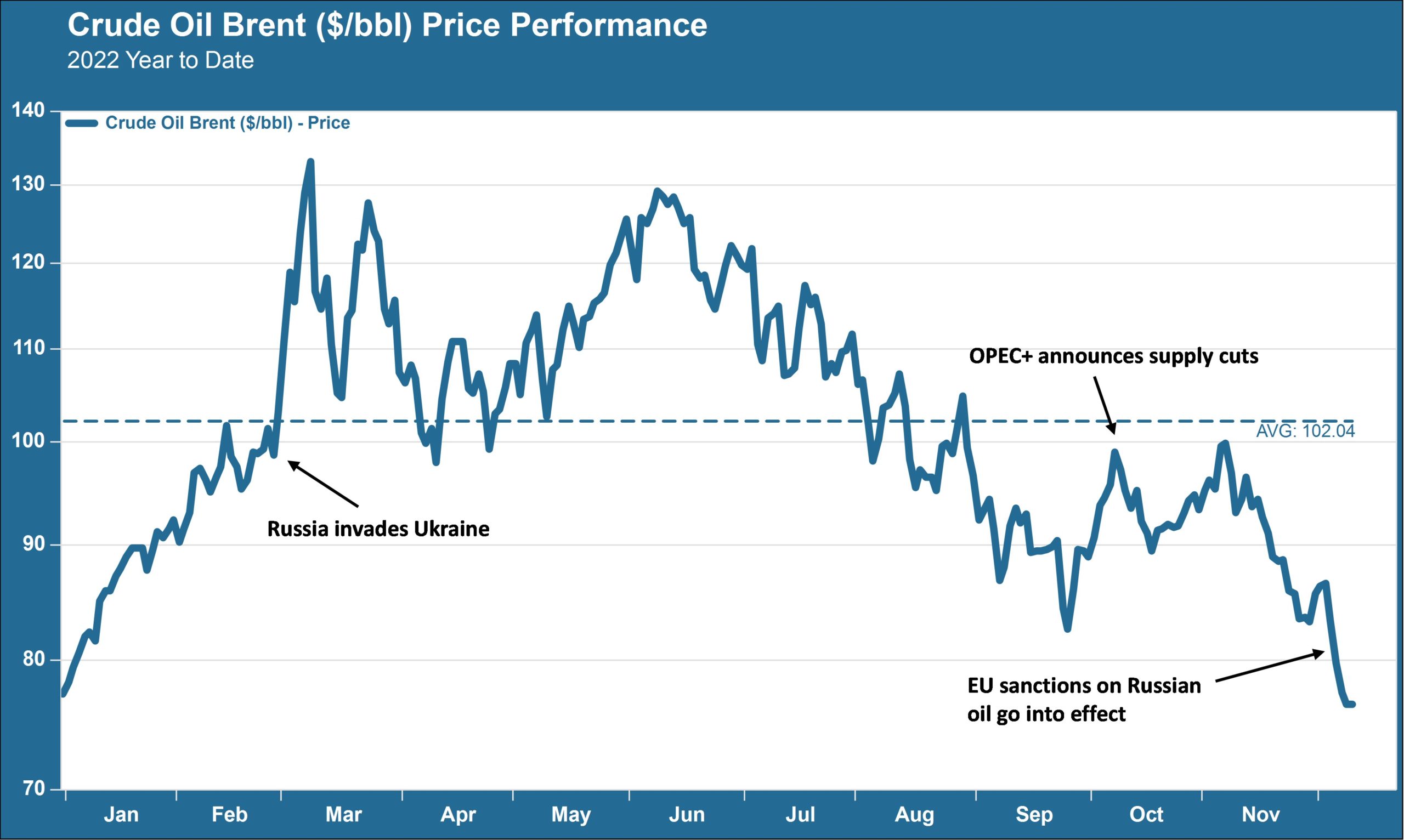

So, here’s a good conversation starter for today: the average price nationwide for a gallon of regular gas today is $3.29. On January 3, the first workday of 2022, the average nationwide price was…yep, $3.29. At the end of a year in which gas prices loomed large over monthly household budgets and struck fear into the hearts of politicians running for office, we are basically right back where we started from. In fact, the spot price for a barrel of Brent crude oil, a market benchmark, is actually down for the year to date.

Supply Surprises

Oil’s downward trend over the past two months is one of more counterintuitive developments we have seen this year. On October 5, OPEC+ nations agreed to a new round of production cuts in the amount of 2 million barrels per day. That was a significant enough supply cut to draw sharp criticism from the Biden White House, accusing the cartel of shortsighted profit-seeking and even interfering with the runup to the US midterm elections. In fact, oil prices fell in the immediate wake of the OPEC+ decision, with Brent crude dropping about $10/bbl before briefly resuming an upward trend (see above chart).

This week saw another potential landmine that many observers thought would send oil prices higher. On Monday the European Union’s sanctions prohibiting entry of seaborne Russian oil into European ports went into effect, along with a price cap, supported by both the EU and the G7, of $60 on any Russian oil sent by tanker anywhere in the world. These punitive measures could have had the effect of Russia sharply curtailing its supply; the country has claimed it will refuse to deal with any buyer who uses the price cap. Instead, the oil has flowed largely unimpeded, at least so far. Asia’s principal buyers of China and India already pay less than $60, effectively, for the oil they negotiate from Russian supply sources. In fact, the $60 price cap was designed in such a way to produce precisely this outcome, while avoiding dramatic supply cuts (it remains to be seen whether that will still be the case if world oil prices shoot back up to $100 and buyers attempt to hold Russia to the $60 cap).

Another positive factor on the supply side has been increased production here in the US. Domestic production plummeted immediately after the economy shut down in March 2020, and producers have been very slow to turn the taps back on. But the number of active US oil rigs is now back to where it was right before the bottom fell out: today’s active rig count of 627 is roughly comparable to the 624 rigs operating on March 27, 2020 according to data produced by Baker Hughes (cited in an article by Catherine Rampell in today’s Washington Post).

Demand Doldrums

On the flip side, demand trends are also helping to put downward pressure on oil prices. China, the world’s second-largest oil consumer after the US, is set to use less oil in 2022 than it did in 2021 according to the International Energy Association. Persistent lockdowns from China’s zero-Covid obsession have had a material impact on demand. While those restrictions appear to be loosening, it may be a very bumpy road for China as it tries to reopen – Covid cases there are surging now, natural immunity levels are weak and China’s domestically-produced vaccines are not up to the task of beating back the many new faces of the omicron strain.

Elsewhere in the world the economic outlook is turning down; the IMF and World Bank both issued new warnings today about growth prospects for next year. There is by no means any certainty that the US is headed for recession next year, and we have noted in several recent commentaries the ongoing conflicting signals from the labor market, consumer spending and elsewhere. But the Treasury yield curve is currently inverted more steeply than at any time since 1981, suggesting that the bond market is quite confident about an impending downturn (though risk spreads, which we would expect to widen appreciably ahead of a recession, have remained relatively tight). US oil demand for this time of year is as low as it has ever been in the past 20 years.

All of this could change, of course. If China manages to stay on course with its reopening that will likely provide some upward momentum for oil prices. Russia still is a wild card despite the relatively muted first few days of the new sanctions. And if the US does manage to achieve a soft landing with the Fed’s monetary tightening – which would be good news on many fronts – we would expect oil demand to turn up here as well. For now, though, you can probably expect fewer of those “how ‘bout them gas prices!” conversations at the water cooler, and a return to the usual observations about weird weather, college football playoffs (or the World Cup, take your pick!) and the traffic jams on the Beltway.