Pundits who follow financial markets are always ready to supply a narrative to the crisis of the day. “Stocks fell today because of X” is how the story usually goes, although “X,” whatever it may be, is likely only a strand of a larger fabric. These days market-watchers are focused on Turkey, and the “X” factor giving the story a human face is one Andrew Brunson, a North Carolina pastor who for the past two decades or so has lived in Turkey, ministering to a small flock of Turkish Protestants. Brunson was caught up in a 2016 political backlash following an attempted military coup, and has been detained on charges of collaboration (unfounded, he claims) against the Erdogan regime ever since.

Earlier this month the Trump administration anticipated Brunson’s release after protracted negotiations. Instead, the pastor was placed under arrest. The US responded with a new round of sanctions, including a 50 percent levy on imported steel. Team Erdogan dug its heels in. The currency collapsed and – voila! – the summer of 2018 now has its official crisis. For investors, the pressing question is whether this is an isolated event, or a larger peril with the potential to turn into a 1997-style contagion.

Shades of 1997

Once seen as the next likely candidate to join the European Union and pursue the traditional path to prosperity by linking in to the global economy, Turkey instead has become a dictatorship under Erdogan. Possessed of a less than perfect understanding of macroeconomics, Erdogan has doggedly refused to address the country’s currency crisis by raising interest rates, the normal course of action. Facing down external borrowing needs of $238 billion over the next twelve months, the regime improbably imagines relief coming from comrades-in-arms such as China, Russia and Qatar. These are Turkey-specific problems.

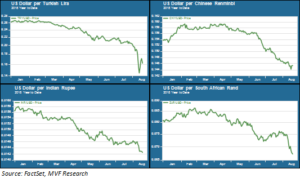

But currency woes are anything but local-only. Almost all major emerging markets currencies are having a terrible time of things in 2018. The chart below shows four of them, including the Turkish lira.

From this standpoint, the situation looks less like a simple tempest on the Bosphorus, and more like the summer of 1997. That was when Thailand, under speculative attack from foreign exchange traders, floated its currency and sparked a region-wide cataclysm of devaluations and stock market collapses. One of the issues contributing to the mess in 1997 was the vulnerability of countries with large amounts of dollar-denominated external debt – a falling currency makes it increasingly difficult to service interest and principal payments on this debt.

This is an issue of relevance today as well; indeed, countries with the largest non-local debt exposures have been hit hardest alongside the lira (see, for example, the South African rand in the above chart). Another theme of 1997 was current account deficits, a particularly important data point for countries where exports play a central role in growth strategies. That has been the driving force behind India’s currency woes this year (also shown above). High oil prices (a key import item) have raised India’s trade deficit to its highest level in five years. And, of course, the specter of a trade war looms over all countries active in global trade.

Sleepless in Shanghai

Arguably the biggest difference between 1997 and today is the role of China in the world’s economy. Back then the country was still in the early stages of the boom that spawned the great commodities supercycle of the 2000s. Now it is the world’s second-largest economy (and the largest when measured in purchasing power parity terms). China is currently dealing with its own growth challenges – very different from those facing trade deficit-challenged economies like India or near-basket cases like Turkey, but concerning nonetheless. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets have been in bear market territory for much of the summer. China’s biggest challenge is managing the transition of its economy from the fixed investment and infrastructure strategy that powered those supercycle years into a more balanced, consumer-oriented market. That is the right thing to do – the infrastructure approach is not sustainable for the long term – but concerns about the transition persist even while the country putatively continues to hit its GDP growth targets.

So how much contagion risk is there? The main problem as we see it is not that the detention of a pastor in Turkey could bring down the global economy. It is that all these strands – debt exposures, trade deficits, growth concerns, trade war rhetoric – are percolating to the surface at the same time. The story is not as systemic as that of the ’97 currency crisis, where the same one or two problems could be ascribed to all the countries suffering the drawdowns. But with all of these strands front and center at the same time, we cannot rule out the potential for broader repercussions.

The ’97 crisis had only a limited impact on developed markets. US stocks paused only briefly before resuming their manically bullish late-1990s ways. So far, neither turmoil in Turkey nor sleepless nights in Shanghai are having much impact on things here at home. A little more volatility here and there, but stocks within striking distance of January’s record high for the S&P 500 (and still setting new highs when it comes to NASDAQ). But we’re closing in on the always-important fourth quarter, and need to be fully cognizant of all the different narratives, positive and negative, competing for attention as the lead theme.