For almost the entirety of the Fed’s monetary tightening program, the relationship between the central bank and the bond market has been like that of a mother insisting that her child eat his vegetables before he can have dessert. The market wants to skip the vegetables and go straight to the cookie dough ice cream. Well, on Wednesday this week Fed chair Jay Powell looked at the kid’s plate, saw that it still had vegetables on it, but decided to bring out the ice cream anyway.

Here Comes Santa Powell

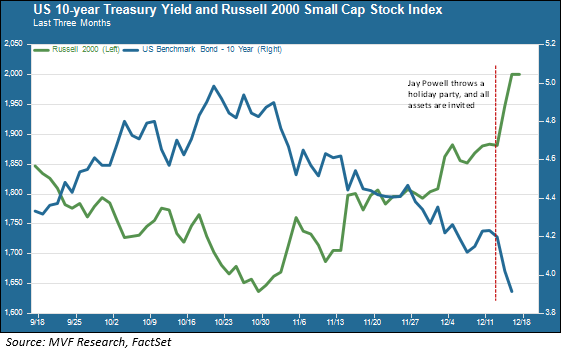

Yes, the pivot has arrived. Wednesday’s meeting was a “dot plot event” in which the members of the Federal Open Market Committee make their best guesses as to where key numbers in the economy will be for the next three years, including the Fed funds rate. These are the Summary Economic Projections. On Wednesday, bond investors skipped over every single estimate in the SEP to focus on one single collection of dots – those representing where the Fed funds rate will be in 2024. Lo and behold, the median estimate was 4.6 percent. Translated into market-speak, that suggests three rate cuts of 0.25 percent each are now the base case for the Fed’s planning purposes. Needless to say, the market was off and running for all manner of investable assets.

Game-Day Audibles

To say that the Fed’s pivot was unexpected would be an understatement. As recently as last week, Fed officials were hammering away at the same points they have been making for many months: the fight against inflation is far from over, and rates are going to stay higher for longer. In fact, with financial conditions having eased significantly over the course of the broad-based November rally, the thinking was that if the Fed pulled any surprises at all, they would be of the hawkish rather than the dovish variety.

So what changed? Not much seemed to be different in the rest of those SEP dot plots, representing Committee members’ guesses about the labor market, GDP growth or longer-term inflation, from what they were in September. There was one notable change, though. The inflation estimate for 2023, i.e. the year that ends in just 16 days, was lower than the September estimate. Part of that was due to a better than expected reading from the Personal Consumption Expenditures index a couple weeks ago. Part of it, though – and this was in Jay Powell’s own words at the post-meeting press conference – was a softer number from the Producer Price Index that came in the same day – Wednesday – as the FOMC meeting. In other words, according to Powell, a few Committee members came into work on Wednesday morning, read the PPI report, and promptly revised their inflation outlooks down. A game-day audible, so to speak. Sometimes those work. Sometimes they will seem in hindsight to have been misguided.

The Puzzle

So what does all this potentially mean for the markets? The sugar high won’t last forever, though we think it’s likelier than not to give an added boost to the positive seasonal vibes historically associated with December. The S&P 500 is just one or two good days away from surpassing its last record high, set on January 3, 2022. We will not be surprised to see the benchmark index close out the year in record territory.

Going into next year, though, the picture is a bit foggier. Both the stock market and the bond market have rallied strongly for seven weeks now. By some technical positioning measures they are at their most overbought levels in more than a decade. Weekly equity inflows are at their highest levels in two years. That could potentially lead to a pullback of sorts in January, and perhaps give investors pause to think through what all this really means.

For one thing, are those rate cuts actually going to happen, and if so, why? Bear in mind that the SEP numbers do not represent policy decisions; they are nothing more than best guesses and they are subject to change. Here’s the thing: the Fed will tend to be more aggressive about rate cuts when (a) inflation is convincingly under control; and (b) the risk of recession is high. Right now neither of those conditions apply. The November PPI number notwithstanding, core consumer inflation is still well above the Fed’s two percent target.

As for the broader economy, it is still growing, even if the pace is likely to slow considerably from the third quarter’s blistering 5.2 percent real growth rate. In other words, the evidence is not yet in that the economy needs even one, let alone three, rate cuts in 2024. The bond market, ahead of its skis as always, has already priced in not just three, but six rate cuts next year. Some caution is merited.

Then there is the added X-factor for 2024 in particular, which is that it is an election year, and the Fed as a rule errs on the side of caution when the political cauldron is aboil, so as not to invite accusations of favoring one side or the other.

All of this is to say that, while we will be perfectly pleased to see the end of the monetary tightening program, we remain considerably less convinced than Mr. Market that the days of easy money and good times for low-quality assets are back. 2024 is likely to have plenty of tricks up its sleeve.