If you spend any time listening to professional economists opining on what lies in store in the months ahead, you would be forgiven for coming away confused. Are we heading into a recession? Maybe, maybe not. It is entirely possible that the real rate of GDP growth for the second quarter will come in negative when the report comes out later this month. The Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank runs a predictive model called GDPNow, which forecasts a decline of 1.9 percent for Q2 GDP as of today.

But that prediction is well below the consensus estimate of about 3 percent positive growth supplied by Blue Chip Economic Indicators. Indeed, the lower band of the Blue Chip forecast, which is an average of the 10 lowest estimates in that survey, still comes in at just below two percent positive growth. Everyone’s looking at the same numbers, but coming up with different predictions. What gives?

Fields of Distortion

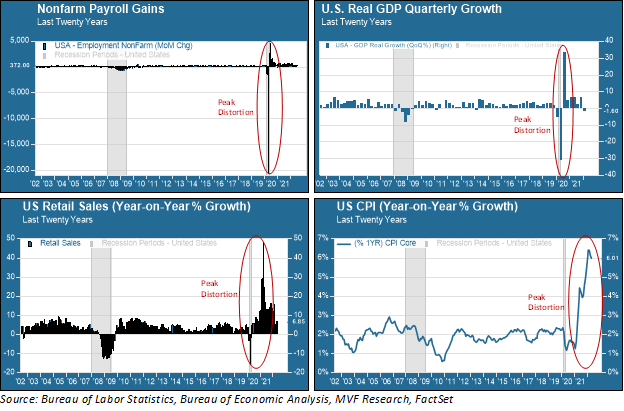

Making light of economists’ predictions, of course, is low-hanging fruit for comedians who feed off the quirks and foibles of financial markets. “They’ve predicted ten of the last five recessions” or variations thereof goes a popular line among Wall Street’s would be Borscht Belt wags. But spare a thought for the practitioners of the dismal science, for they have been dealt an unkind hand by the gale-force winds of distortion in the past couple years. Consider the following chart, with a selection of key macroeconomic indicators going back twenty years, to see what today’s economists have to try and make sense of.

Simply put, the economy’s performance since the pandemic began bears no resemblance to any previous period since the numbers started to be compiled and presented in a meaningful way after the Second World War. After the longest growth cycle on record, from 2009-20, we had the shortest recession on record. That recession, which saw the deepest fall in GDP since the Great Depression, was followed by a furious influx of fiscal and monetary stimulus leading to the off-the-charts numbers for retail sales (bottom left chart above) and, eventually, inflation (bottom right).

None of this was natural and organic – not the decision to shut down the economy, not the decision to put government money directly into the bank accounts of households and businesses, and not the decision by the Fed to park interest rates at zero and promise to buy whatever securities it had to in order to keep financial markets afloat. When you look at these numbers and others like them (e.g. the unprecedented increased in the M1 money supply), how are you supposed to make an empirically sound forecast for what comes next?

More Secular Stagnation?

Some are making the case that the most likely outcome for the post-distortion economy will be a return to what we had in the 2010s – below-trend economic growth, a return to subdued wages and lower price inflation, and an activist Fed ready to prime the pump with easy money in order to grease the wheels of the financial system. There is a coherent logic to this case. In the 2010s it was a combination of low productivity, an aging population (lower labor force participation rate) and businesses opting for shareholder givebacks over new capital investment that facilitated subpar growth and moribund wage or price inflation. Neither productivity nor demographics have visibly changed much since then. Nor do businesses appear to have lost their appetite for stock buybacks as a way to goose earnings per share and keep the investment community satisfied. Why should the natural economic trajectory look any different?

The Fog of Transition

While we agree with some of the insights for a return to secular stagnation, we are skeptical of the overall argument that the latter 2020s will much resemble the previous decade. For a great many reasons, by no means all of which have to do with economics and markets, it is a different world today. One of the key ways in which it is different is that the background context of globalization is considerably more tenuous than it was five years ago. World trade as a percentage of world GDP has steadily declined, relations between the two leading economies (the US and China) have become ever more adversarial, much of the growth in emerging economies (in particular those outside of Asia) has stagnated or gone into reverse, and national political institutions in large and small countries alike are in disarray or outright decay.

What happens in the immediate post-distortion economy, in our opinion, is a murky transition – perhaps the closest point of comparison would be the transition from the postwar Bretton Woods economic framework to the globalization, privatization and financialization that took root and grew in the 1980s and 1990s. We expect there will be upsides and downsides to this transition, and potentially transformative developments that ultimately shape a new economic order.

But that’s all in the future. For now, we see the “inflation surprise” period of the post-distortion economy stabilizing and starting to recede, while the “growth surprise” element is more likely to move into the foreground. Earnings season starts next week, and that will be a good warm-up act for the Q2 GDP number we get on July 28.

There is both upside and downside potential in terms of how alternative growth scenarios feed into market sentiment. It would be wise to pay little heed to anyone who tells you they know with high confidence what that means for the next six months on the S&P 500. But growth – or the lack of growth – is going to shape the contours of market opportunities as we head into the middle years of the decade.