Our title for this week’s piece, “The Recession Trade,” could mean a couple of different things. You could take it literally, in the sense of trying to plan a successful financial trade around a potential recession. You could also interpret trade as “plying one’s trade,” as in deciding that it is your job – your trade – to wake up every morning and talk all day about the recession that surely must be just around the corner. Many members of the financial village, from media talking heads to economists of various stripes, seem to be trying to make a living out of willing a recession into existence.

We address both of these interpretations here. Everybody’s talking about a recession, which could in fact hasten the timetable for one showing up. And if the daily chatter gains in intensity, the probability increases that investors will act like it is already here by selling out of risk-on assets. If this is the case then the recession trade – in the “do something” sense of trade – would be to take a more defensive position by decreasing or hedging the riskier asset components of your portfolio. But there is a caveat to that as well. We’ll take a look at the evidence first, and then come back to the caveat.

Recessions and Markets

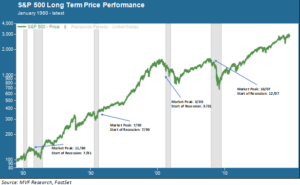

If a recession does happen, there is a pretty good chance that the high point in the stock market will have already come and gone. Consider the chart below, showing the price trend of the S&P 500 since 1980. The gray shaded areas represent each of the recessions the US has experienced during this time.

In three of the five recessions that have occurred since 1980, the stock market started falling well ahead of the actual start of the recession. When you hear financial pundits talking about “getting out ahead of the recession,” they most likely have in mind one of these occasions. In 1980 the S&P 500 peaked fully nine months ahead of the recession that began in July 1981. After the late-1990s tech bubble hit its record high in March 2000 the broader economy moved along in positive growth territory until turning negative a full year later. And the market peaked two months before the recession of 2008 began.

This could be another one of those instances. The market has more or less gone sideways for the last twelve months – the S&P 500 closed at 2,914 on August 29, 2018 and it looks set to close somewhere around 2,925 today, August 29, 2019. The trade war is here for the foreseeable future, corporate earnings are trending negative and management teams are guiding expectations down as they present their near-term outlook on quarterly earnings calls. The consensus sentiment seems to be talking itself into a recession well before the stage is actually set for two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. Now would seem to be a good time to dial back a bit on risk exposure, right?

And Now, the Caveat

Unless it’s not. Here’s the caveat we promised to get to. There have been five recessions since 1980. There have been a grand total of 11 recessions in the 74 years since the end of the second world war. Statistically speaking, that’s not a whole lot to work with. Consider that chart above. In the recession of 1990 the market peaked right at the same time the recession started (July 1990) – there was no lag time at all. In the recession of 1980 the market didn’t even register a correction-level pullback. Moreover, in the cases of 2001 and 2008 the driving forces behind the respective market crashes of those times had less to do with traditional business cycle dynamics and more to do with highly unique circumstances – tech stock valuations in 2000, and the overleveraged credit derivatives markets of 2008.

Long story short: there may be any number of reasons to take a more defensive position in equities today. Volatility has been and remains elevated. A bit of insurance could make sense for a concerned investor with an all-equity portfolio – for example, by building a small cash position or hedging with equity put options throughout the often tricky months of October and November. A diversified portfolio with a mix of stocks, bonds and alternative assets, on the other hand, already has some insurance built in and may not require much or any additional action. There are lots of factors at play and some of them have little or nothing in the way of historical precedent. These are, in the sense of the old Chinese curse, interesting times.

But there simply is very little in the way of empirically sound data to support the idea of a “recession trade” simply based on previous patterns of markets and recessions. Statistically speaking, there are no patterns because there is not a sufficient sample size of events from which a pattern could be inferred. The best recession trade, in fact, may be no trade at all.