As portfolio managers, we at MV Financial establish benchmarks against which to measure the performance of assets under our management over time. We do this not to obsess over short-term performance – most of our portfolios are established with long-term financial goals and risk considerations in mind – but as a way of getting hard-nosed feedback from the market to either reaffirm or challenge our prior assumptions and make informed changes appropriately. Consistent with our own investment philosophy, we employ two primary benchmarks: a risk benchmark that mirrors the risk-adjusted objectives of our strategic models (ranging from a strong growth orientation to income preservation), and a style benchmark that incorporates the different asset classes we typically employ for purposes of prudent diversification. This approach works well in our opinion and helps guide constructive performance review discussions with our clients.

The Wall of 60/40

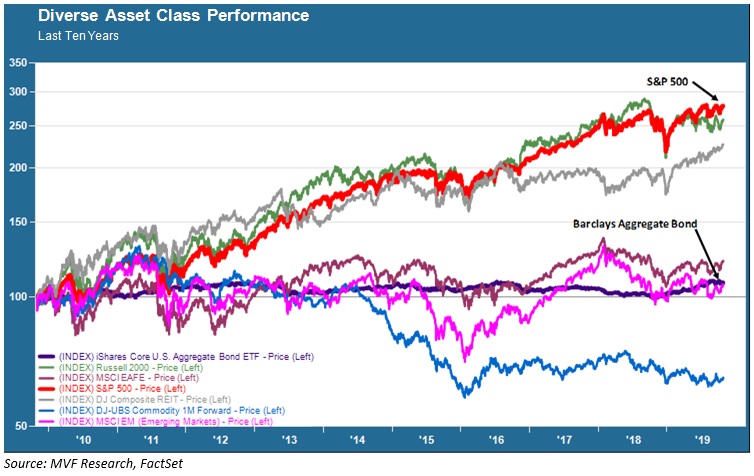

But there is an inescapable reality that increasingly seems to be an indelible feature of the global capital markets: practically any benchmark that incorporates some mainstream asset class other than large cap US equities and intermediate-term US bonds will very likely fall short of a simple large-cap stock / bond mix over practically any measurable period. The age of the relentless benchmark – encapsulated in its simplest form by some percentage mix of the S&P 500 and Barclays US Aggregate Bond index (e.g. 60/40) – is upon us. Will it haunt portfolio managers forever, or is there still such a thing as mean reversion? It’s our business to analyze phenomena like this, figure out what it implies for our investment philosophy and portfolio construction methodology, and share our thinking with our clients.

The Ageing of Modern Portfolio Theory

For as long as anyone managing money today has been around, the bedrock of portfolio construction has been Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), the origin story of which traces back to a paper in the Journal of Finance magazine by University of Chicago Professor Harry Markowitz in 1952. MPT has evolved somewhat over the ensuing years, from simple Markowitz mean-variance analysis to the three-factor models of Kenneth French and Eugene Fama in the early 1990s that in turn pointed the way to the abundance of factors touted by the quant-driven strategies on offer today. But the core of MPT has remained largely intact: asset class diversification aimed at achieving the optimal level of return achievable in the market for a given accepted level of risk (where risk is defined as the magnitude of variance around the average tendency of returns). The so-called “efficient frontier” is supposed to look like a more or less linear progression from ultra-safe assets like short-term Treasury securities to volatile categories like emerging market equities and illiquid venture capital.

Beware of Central Bankers Bearing Gifts

The efficient frontier has been about as robust a frontier in recent years as the French Maginot Line in the Second World War (i.e., not able to withstand assault). Up to a point, investors get additional return for their incremental assumption of risk. That point, to be specific, is US large cap stocks. The chart below illustrates this phenomenon. It shows the ten-year trendline for the S&P 500 (the thick red line) and for the Barclays Aggregate Bond index (the think dark purple line) against a handful of other asset classes. All the other assets – from REITs to small cap stocks, developed and emerging non-US markets and commodities – are riskier than large cap stocks and bonds (again, as measured by volatility around expected returns).

The uselessness of the efficient frontier over this ten-year period is perhaps best illustrated by looking at that relative performance of emerging market stocks – the riskiest asset on that chat represented by the pink line – and the least-risky alternative of US bonds. In terms of absolute cumulative performance, these two asset classes returned almost exactly the same over this period. Taking on all that additional risk to invest in emerging markets, it turned out, bought you no incremental performance gain over investing in safe, plain-vanilla bonds. For an entire decade.

There may be many explanatory factors at work here, but one looms large above them all: easy money from central banks. The coordinated dovish policies of global central banks over the last ten years brought about two accomplishments: first, maintaining continual downward pressure on interest rates (which in turn makes bond prices higher) and, second, pushing traditional fixed income investors out of their usual safe habitats into riskier assets.

But “riskier” only up to a point. When we say “traditional fixed income investors” we are talking about the likes of insurance companies and pension funds: large institutional investors with very conservative investment policy mandates. Disappearing bond yields required these investors to go further afield, but they were never likely to venture too much past high quality, dividend-paying large cap stocks. Hence the disruption of the risk frontier at the point of US blue chip stocks and the relative underperformance of all those other, riskier asset classes. The disruption comes courtesy of the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of Japan.

So have central banks slayed Modern Portfolio Theory for once and for all? We would not bet on it. The monetary policy phenomenon of the past ten years is already showing signs of wear and tear. At some point the Great Bull Market of the 2010s will come to an end, and at some point thereafter a new one will rise. We know neither when nor how any of this will come to pass. But when it does, we would imagine it more likely than not that the relationship between risk and return will look more like the efficient frontier of old than the domineering 60/40 wall of today. But those will be decisions for a future day. The more immediate task is to prepare for what we believe will be a tricky set of currents to navigate in 2020, which has the potential to be a very strange year indeed.