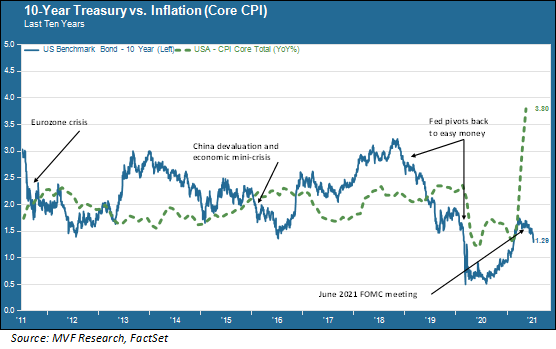

Yes, it’s another column about the bond market after a few weeks where we turned our attention elsewhere. But we’re still trying to make sense of a trend that we wrote about a few weeks ago that has only gotten stranger since – and we think it is one of the more important stories out there deserving of our attention. We’ve updated the chart from that earlier commentary here below.

Inflation and Yields

The above chart shows the long-term relationship between the yield on the 10-year Treasury note and inflation, represented here by the core (excluding food and energy) Consumer Price Index. Over time this relationship tends to be relatively stable; the natural place for nominal bond yields, according to the finance textbooks, is at some premium to expected inflation with the size of the premium subject to various economic factors. At various junctures this relationship may not hold; for example, when market shocks drive up demand for safe haven assets (for example September 2011 and January 2016) or when the Fed abruptly pivots on its monetary policy direction (for example January 2019 and March 2020).

Starting in late 2020 inflationary expectations started to build as investors factored in the variables of successful Covid-19 vaccines, an expected resulting surge in consumer demand and ongoing supply chain problems impeding the ability of businesses to fully satisfy this rebound in demand. Quite rationally, interest rates began trending up. This trend gathered steam in the first few months of 2021 as the additional variable of unprecedented levels of fiscal relief and stimulus from the new Biden administration got thrown into the mix.

Throughout this period the official stance of the Fed was that higher inflation would be a temporary phenomenon related to the immediate post-pandemic environment, and that things would quickly settle back down to a world of long-run inflation in line with the central bank’s target rate of two percent. The go-to narrative among the financial chattering class in the first quarter of 2021 was that the bond market wasn’t buying the Fed’s assurances; that inflation was a bigger problem than just a couple months of anomalous supply-demand dynamics and that the Fed would eventually have to play catch-up.

Inflation and Growth…Or Not

That narrative appears to have been turned on its head. This week the 10-year Treasury fell below 1.3 percent, continuing the downward trend that followed the June FOMC meeting. Now it seems to be the bond market saying that inflation is no big deal, while at least one faction of the Fed – according to the FOMC minutes released earlier this week – is becoming more vocal about the possibility that monetary tightening may need to happen sooner than planned. It’s like one of those switcheroo movies where the mom and her 13-year old daughter wake up to find themselves in each other’s body.

Lurking in the background of all this is the specter of the kind of economy we experienced in the 2010s, characterized by perennially low growth, below-trend inflation, low unemployment with stagnant wages and dependence on the Fed for easy monetary policy. If the collective wisdom of the bond market is that once the dust settles from all the pandemic-related distortions then this is the world we’re going back to, then yes – a 10-year yield around 1.3 percent and 30-year rates below two percent make a certain amount of sense. The potential growth component from population and demographic trends hasn’t improved – the rate of population growth continues to shrink as does the percentage of the population in the labor force. Productivity, the only other source of sustainable economic growth, has yet to demonstrate a meaningful reversal of structural weakness.

So the bond market may be reflecting peak growth and inflation. Or, the recent trend may be due to temporary technical factors and indicative of nothing as far as longer-term dynamics. Either way, it’s a pretty good bet that this won’t be our last piece on the subject.