In some ways our commentary this week picks up from where we left off last week, but we’re extending our gaze from the sudden shocks of the present out to what is increasingly likely to be the slow stagnation of at least the intermediate future. Our discussion last week about the “bad news is good news” mindset on Wall Street played out in all its glory this morning, with the much-anticipated release of the monthly jobs report for April from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Pictures Worth a Thousand Words

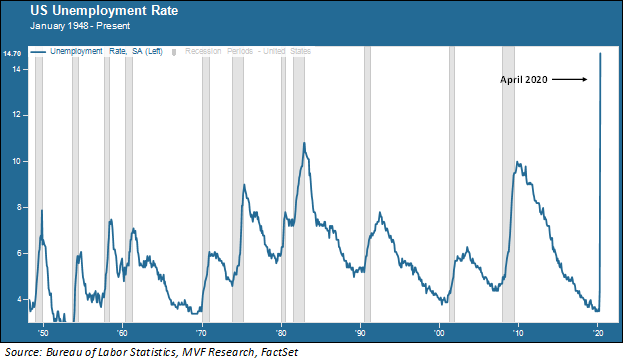

The BLS has been keeping records since 1948. What most economists and other observers focus on every month are two numbers: the headline unemployment rate, and the net change in monthly payroll additions or subtractions. Here below are charts showing both of those numbers for this entire history of 1948 to the present day, starting with the headline unemployment rate:

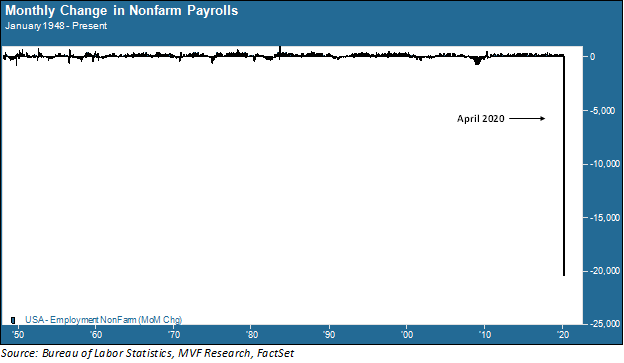

The following chart showing the monthly change in payroll data is probably the most visually unsightly chart we have ever posted. There’s no way to nicely harmonize all that blank white space given the magnitude of this month’s change versus anything in the past.

Having read our commentary last week, you are of course by no means surprised that traders danced a little jig and put on their “buy” hats when the BLS report came out. These April numbers were actually a little bit better than the consensus estimate which expected 21 million payroll losses (as opposed to 20.5 million) and a 16 percent unemployment rate versus the actual 14.7 percent result. Again, there is a certain logic here: with the economy starting to open back up, the expectation is that 14.7 percent is as bad as it gets – we can quantify the damage and move on to better days. But the logic is short-sighted. Looking ahead is the right thing to do – but what is slowly emerging is something quite different from the back-to-normal-in-a-flash sentiment that continues to drive stocks higher.

Structural Stagnation

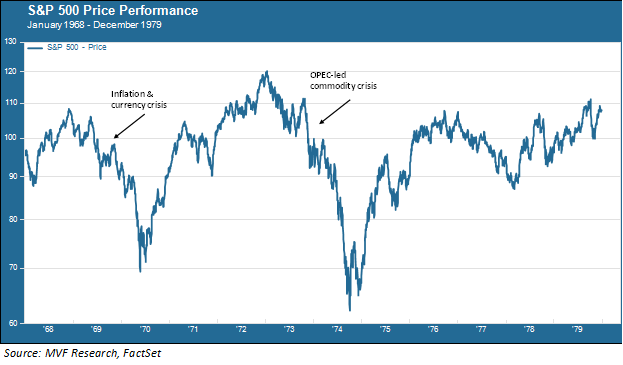

“Stagflation” is a term frequently used to describe the economy of the 1970s. That economy was hit by a pair of crises in the early years of the decade: an inflationary and currency crisis that began in the late 1960s and culminated in the US withdrawal from the Bretton Woods gold exchange standard in 1971, and a commodity crisis when OPEC raised the price of oil by five times its previous level in 1973. When these events happened they were seen as shocks to the system. But then, as always, the capacity of human imagination did not proceed much further than the standard line of “how long till we get back to the way it was before?” Today we are again digesting the impact of a shock to the system, and again we are largely preoccupied with asking that same question. Now that we know how many people are out of work, how long do we have to wait until the economy can party like it’s 2019?

The stock market during the course of the 1970s experienced successive rounds of selling waves and relief rallies, as the chart below shows.

This pattern suggests that things did not go back to the “way things were” and in fact we know they didn’t. Things stumbled along for the rest of the decade; it would not be until 1982 that the stock market was able to regain and sustain itself above the market’s high point in 1968. What did happen was that the prevailing ideas of the time – state owned enterprises, rigid government controls on a wide spectrum of industry sectors and other manifestations of the dirigiste Bretton Woods framework fell out of favor, as did the politicians who espoused them. Along came a new set of ideas around privatization, deregulation and globalization – and the economy has been built around that consensus ever since.

Something new will eventually emerge from this current period. For the intermediate term we are likely to have higher structural unemployment, consumer spending at a more hesitant pace than usual and cautious levels of business investment as companies wrestle with the impact of likely global decoupling on their tightly interlinked supply chains. The conventional ideological wisdom of the globalization era was already under attack well before the coronavirus hit. All this suggests to us that, while there will be periods of opportunity and periods of risk in the months ahead, it is likely to be a bumpy ride, and perhaps something along the lines of the repeated booms and busts of the 1970s. We may not get too many more visuals as dramatic as this week’s unemployment results, but there will be plenty of structural uncertainty.