It’s a regular part of our job, day in and day out. We wake up, plug ourselves into the highways and byways of the global news feed, and absorb everything we can about whatever may have an impact on financial markets. Then we sit back and inevitably say something along the lines of “wow, that’s just crazy” or “we live in strange times” or “live long enough and you’ll see everything.” In financial markets, of course, there is always a lively debate between people – some of whom are experts and some of whom are the guy at the end of the bar spouting out some or other pet theory about how the world really works – about where the market is headed. Sometimes, to be clear, the guy at the bar gets it right when the experts don’t.

When things get really exuberant – and let’s be serious, things have been really exuberant since, oh, round about March 24, 2020 after the Fed came riding to rescue us all from the pandemic – the talk often turns to how much longer the craziness can continue. Junk bonds and crypto and meme stocks, oh my! Surely this is all going to end badly, and soon, right? History suggests that all trends eventually come to an end. But soon? Don’t count on it.

Bull Interrupted, Bull Resumed

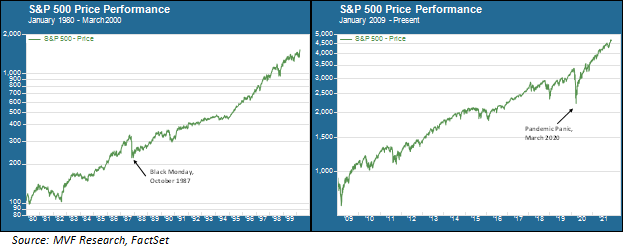

We thought it would be instructive to put two very impressive bull markets side by side and think about what these charts are telling us. We also play a bit fast and loose with the term “bull” rather than sticking to the pedant’s insistence that a bull run technically ends when the market falls by twenty percent or more from its previous high. Think of it as a “macro growth” market rather than a bull market, if you want to get all technical about it. Anyway, the comparison is between the growth market that ran from 1982 to 2000, and the one that started in 2009 and is still going strong.

What do these two markets have in common? For one thing, they both experienced at least one big interruption. The 1980s bull run had Black Monday, the day in October 1987 when US equity markets lost more than twenty percent in a single day – the worst single-day bloodbath ever. More recently, of course, the market that ran throughout the entirety of the 2010s got caught flat-footed by the coronavirus pandemic and lost almost 35 percent of its value in March 2020.

The second thing they have in common is that the growth trend resumed almost immediately after the crash. Nothing of any major import happened in the US economy in the latter part of 1987 apart from the market crash. No recession, no geopolitical blow-up, nothing. The market resumed its winning ways, pushed through the brief recession at the beginning of the 1990s and then got a big refueling when the Internet came onto the scene in the middle of that decade.

The scene was different in 2020 but from the market’s perspective the song remained the same. The pandemic was only just getting going when investors came roaring back into the stock market in the wake of the Fed’s extraordinary actions to stabilize credit markets. Nothing seemed to matter – not the economy shutting down, not the hospitals filling to overcapacity, not the sobering daily fatality count – as the market sailed ever higher on the Fed’s easy money tailwind.

Things Look Great Until They Don’t

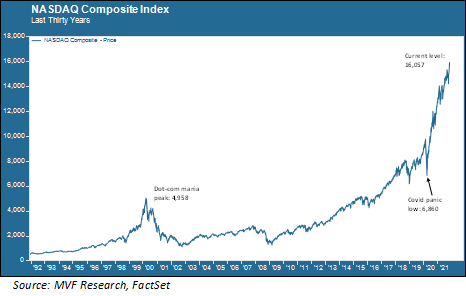

In the late 1990s much of the daily market chatter sounded like what we hear today, with pundits shaking their heads at the latest gobsmacking results from a dot-com darling with no earnings going public and making overnight millionaires out of Silicon Valley coders, developers and administrative assistants. How much longer can this go on, they asked. They were asking the question in 1996, the year of then-Fed chair Alan Greenspan’s famous “irrational exuberance” quote. They were asking in 1997 when Asian currencies plunged, taking the entire emerging markets asset class with it. And again in 1998 when hedge fund Long Term Capital Management got caught like a deer in the headlights as Russia defaulted on its sovereign bonds. By 1999 market valuations made the world of September 1929 seem positively rational.

There was no particular reason why the exuberance ran out of steam precisely in March of 2000. Oh, sure, a bunch of VCs started cashing out of their dot-com holdings with the passing of a couple prominent lock-up periods. But the economy was doing just fine, and people kept coming online in droves to chat on Yahoo! or buy books on Amazon or surf the many proliferating news sites. No matter – we know in hindsight that March 2000 was the end of the exuberance. Two years later, the value of the Nasdaq Composite with all those high-flying tech names was worth just a quarter of its value at the peak.

Then again, today the value of the Nasdaq Composite is more than three times higher than its value at the peak of the dot-com mania.

So is the irrational exuberance about to pop? Maybe. Or maybe not. There won’t be a memo, any more than there was on March 31, 2000. There will be the usual collection of sky-is-falling Cassandras and life-is-wonderful Pollyannas making their respective cases. Someone will be right, someone will be wrong, and none of it will have anything to do with a clear-cut argument as to precisely why, to paraphrase one of the great questions of human history, this trading day is different from any other trading day. If you think you are closer to the end of the cycle than the beginning, you may start to make more conservative allocation choices – quality over junk, solid cash flows over quirky memes, modest liquid yields over things that pay out more today but may keep you locked up tomorrow. Follow the daily chatter from a dispassionate distance, keeping the twin evils of fear and greed at bay. Read a good book. Enjoy life.

We wish all of you a very happy Thanksgiving. May the holiday be full of joy, laughter, good conversations and good health.