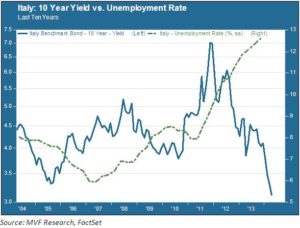

Sometimes a picture can convey a thousand words, encapsulate an entire story. Consider the chart shown below. It shows a ten year comparison of the Italian 10-year government bond yield with the Italian unemployment rate.

The chart shows that while unemployment in Italy is far and away at a ten year high, the yield on the benchmark Italian government bond is far and away at a ten year low. Almost 13% of the population – and a much, much larger percentage of the population of young working-age adults – are out of work and looking for work. The Italian economy is in a precarious state. And yet, investors are buying Italian bonds at a torrid pace.

Mediterranean Roulette

Italy is by no means the only country where sovereign debt weirdness runs rampant. Greece recently came back to the capital markets with a bond issue. The country is essentially insolvent and plagued by political dysfunction (to put it mildly) – but that does not seem to be a problem for Europe’s credit market investors. Spain and Portugal both have 10-year yields under 4%, while more than half of their populations in the 20-30 year age brackets are out of work. It seems hard to make a compelling case for how this will end well. The question to ask – looking at that jaw-dropping chart above – is why peripheral European bonds are looking so attractive. Is this a bubble on the cusp of bursting, or is there a plausible reason why investors are so full of the Mediterranean spirit? Let’s briefly retrace the Eurozone’s trajectory from two years ago to the present.

Whatever It Takes 2.0

The current phase of the Eurozone’s economic journey started in July 2012, with arguably the three most famous words pronounced on the Continent since veni, vidi, vici. “Whatever.It.Takes” said European Central Bank Chairman Mario Draghi, adopting a U.S. Fed-style openness to unconventional means to keep asset prices from falling into oblivion. Several months earlier the Economist magazine, a normally sober publication not given to breathless hyperbole, had predicted the collapse of the single currency region. Draghi’s three-word proclamation banished those fears, and peripheral bond yields began their journey from double digits to today’s gentle levels.

Investors now expect to be compensated for their faith in Draghi. With inflation in most of Europe hovering around zero, expectations are steadily building that the ECB will step in with a new monetary stimulus program. Such a program would likely have the immediate effect of sending bond yields lower. A Eurozone QE may not resemble the one currently being tapered down in the U.S., but the general consensus is that holding Italian paper at 5% or Spanish notes at 3.5% would be a good trade (at least for a while) if a stimulus program were to be announced.

Another Country Heard From

But there is no guarantee that a no-holds-barred Euro QE is in the offing. As is so often the case in Eurozone financial policymaking, any such program would have to first clear a significant hurdle: Germany. The inflation-averse Bundesbank shows little indication of undue concern over current price levels. Mario Draghi has a much tougher, more politically contentious path to enacting policy than does his counterpart Janet Yellen at the Fed.

All of which is to say that now would seem to be a spectacularly bad time to be pouring funds into the European bond market. We have stayed away from this sector for some time now, and we will continue to happily forego any yield-enhancement opportunities coming out of this sector of the credit markets.