It’s reasonable to assume that you have never once driven into a gas station expecting an attendant to come out and pay you for the privilege of filling up your car. Doesn’t happen! But for a brief and very strange moment this week, the price of one particular type of crude oil – West Texas Intermediate (WTI) sweet light crude to be precise – was trading at the never before seen rate of minus, yes, minus $40 per barrel. That surreal snapshot of our weird time caused quite a bit of head-scratching in the financial media this week. But like everything else in economics, this anomaly ultimately comes down to simple supply and demand, and an understanding of how the futures markets work.

Taking Delivery

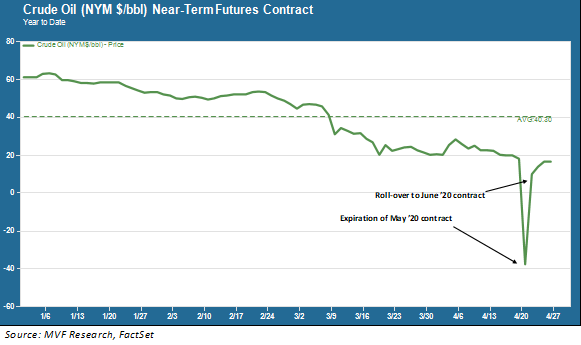

The chart below shows the trend in WTI crude oil prices for the year to date. Specifically, it is the price of the nearest-term futures contract, and that is the key point to keep in mind while trying to digest that sudden plunge into negative territory earlier this week.

Here’s how it works: A futures contract is an obligation to take delivery of some commodity at a specified future date. Commodity futures are a long-established practice, pre-dating even the modern stock market. Five hundred years ago, in samurai-era Japan, merchants traded rice futures on the Osaka futures exchange – and that very same exchange was still around in the mid-1980s when it became the first venue in Japan to trade financial futures based on shares traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

In any event the key variable here is “delivery.” If you buy a futures contract based on crude oil, or soybeans or (channeling our inner Dan Aykroyd in “Trading Places”) pork bellies, and you still hold that contract on its expiration date, you are obligated to take delivery of those barrels of oil, bushels of beans or slabs of pork bellies. Now, in the highly digitalized world of modern futures trading, very few investors ever come into contact with the commodity itself – they sell out or let the contract settle in cash through market intermediaries. Nonetheless, the physical product still exists, and it has to go somewhere.

You Couldn’t Pay Me Enough…

In the case of WTI crude oil futures that “somewhere” is a large storage hub in Cushing, Oklahoma. The problem is that the Cushing storage facility is nearing capacity, due to the sudden plunge in global demand brought about by the coronavirus crisis. It is expected to be completely full within several weeks, coincidentally when deliveries from the May futures contract come due. That May contract actually expired this past Tuesday. Anyone holding the contract after that date would be on the hook for taking delivery – but if they didn’t already lease space at the Cushing storage facility they would have nowhere to put it. Suburban driveways are not exactly equipped to handle a big shipment of barrels of oil.

So as the contract neared its expiration on Monday, sellers had to pay buyers – basically leaseholders with space at the Cushing site – to take the oil off their hands. That’s what caused the price to go negative. But it only lasted for a day, because on April 21 the “nearest-term” contract rolled over from May to June. Since June is farther away than May there is either a chance for the storage capacity issues to be cleared up (not entirely likely) or at least the opportunity for contract holders to buy time. Prices for the June contract traded up from $10 to about $16.50 over the next several days, as the chart above shows. That being said, there is still a perfectly good chance that prices could trend back down and even go negative again if the demand-supply imbalance has not improved appreciably by the time the June contract nears expiration in late May.

The Fog of Global Demand

What we saw in the crude oil market this week is a particularly colorful version of the basic economic challenge we face in this coronavirus crisis. Demand for a wide variety of goods and services has come to a screeching halt with lockdowns and mandatory social distancing. Supply chains are in disarray as producers have no idea how to profitably plan for inventory levels in the months ahead. And the ongoing uncertainty about a reasonable timeline for opening back up frustrates all efforts to make rational, informed choices. In this environment it is important to remain disciplined and not be distracted by strange, seemingly counter-intuitive trends in financial markets. What matters most is getting better clarity on how to manage this pandemic through testing, tracing and, yes, continued distancing measures to get to the other side of this. In the meantime, supply and demand have a failure to communicate.