It has not been much of a year for thinking about different ways to extend portfolio exposure into riskier asset classes. Inflation, geopolitical unrest, dysfunctional supply chains and all the other weekly wet-blanket topics have kept the focus of portfolio managers on protecting the downside. But in this business it is always wise to look ahead, because what goes down will sooner or later go back up again. In that spirit, we turn the spotlight this week to the asset class of emerging markets equities.

A Bit of A Misnomer

Let’s start with the simple fact of what you actually get when you invest in a security tracking a broad-based emerging markets index. MSCI has been at this game longer than just about anyone, and their emerging markets index is pretty much the gold standard of the asset class. What’s in that index? As of the most recent fact sheet through October 2022, a full 69 percent of the index is made up of four Asian countries: China, India, Taiwan and South Korea. The entire remainder the emerging markets world from Latin America to Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and the rest of Asia is lumped into that residual 31 percent. Considering the strategic fundamentals, the MSCI EM index is essentially a bet on the future prospects of Asia’s largest economies (excluding Japan, of course, which graduated from “emerging” status many decades ago, and the financial centers of Singapore and Hong Kong).

Thirty Years Is A Long Time

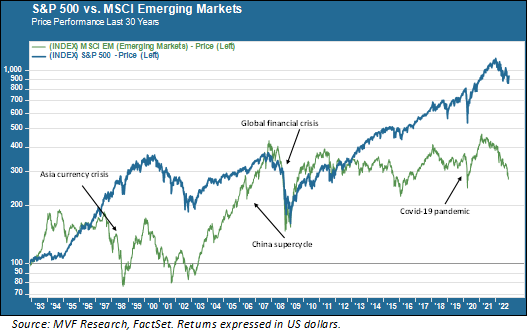

So how have things worked out for this asset class so far? Consider the thirty-year performance of the MSCI EM index versus the S&P 500. Thirty years is a long time and a lot of market cycles – and bear in mind that the entire premise of a high-risk asset class like emerging markets is that by taking on that higher level of market risk, the investor should expect the possibility for higher longer-term returns.

The top-line message of this chart is quite simple: over the past thirty years, from 1992 to today, the S&P 500 has returned more than three times as much as the emerging markets index for a US-based investor (the returns here are expressed in dollars, the home currency of a domestic investor). The corollary to the top-line message is that all that underperformance of returns came with more risk. Consider the Asia currency crisis of 1997 (highlighted on the chart). The EM index plunged and then rallied again in late 1998 – but even after the bounceback the index was below its pre-crisis high. All the while the S&P 500 was steadily surging ahead during the economic boom of the late 1990s.

In the chart you can also clearly see that there have been select periods of strong outperformance by emerging markets, and none more so than the China supercycle era of the early 2000s (also highlighted). This was the period when China surged on its way to becoming the world’s second-largest economy. Even after the global financial crisis of 2008, China, along with other Asian economies, bounced back faster than other parts of the world. But the supercycle eventually ran out of steam during the 2010s as China tried – several times and mostly without much success – to rebalance its economy away from massive state-led expenditures into infrastructure and property development and into consumer spending.

Tactical investing works if you get the timing right, but in our opinion accomplishing that is a matter of luck more than a matter of skill. And you need the favors of Lady Luck twice – not just in figuring out when to get in but, perhaps even more difficult, when to call it quits and get out.

The Almighty Dollar

The other important consideration, true for any investment outside of one’s home currency, is the strength of the dollar. A substantial part of the outperformance of domestic stocks over both emerging and developed non-US markets, particularly in the past decade, has been the dollar’s continued dominance over this period. If you invest in a foreign asset and that asset earns a ten percent return but the currency in which that asset is based falls ten percent against the dollar, then your portfolio statement at the end of that period is going to show a return of zero. Even with the historically low interest rates that prevailed up to the end of 2021, the dollar retained its strength and made it clear that, for the time being anyway, there is no viable challenger to its status as the world’s reserve currency. And that matters when it comes to portfolio choices.

So what about going forward? The world economy seems to be in a different place today than it was for much of this 30-year period, with more hostility and less of the frictionless collaboration characteristic of the peak globalization era. China, for one, is investing heavily in targeted sectors where it hopes to achieve dominance, including clean energy technologies and biosciences. India has put in some solid growth in recent years. Taiwan continues to dominate the global semiconductor industry through its blue chip heavyweight Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which produces around 80 percent of the world’s advanced computer chips (South Korea’s Samsung being the other gorilla in this sector).

One of our core tenets as portfolio managers is that we do not adhere rigidly to ideology. We will never invest or not invest in something because of a preconceived belief system. What we will do is evaluate the data and consider the pros and cons of alternative strategic choices. For now, as we look ahead to where we might allocate more weight to riskier asset classes, we are inclined to look elsewhere than emerging markets. That may change – but for now we think the cons outweigh the pros.