Every profession has its core mantra. The mandarins of medicine solemnly invoke the Hippocratic oath (first of all, do no harm). “Equality under the law” say the Doctors of Jurisprudence. In the practice of investment management, generations of money men and women since the 1930s have been trained thus: “in the long run, value outperforms growth.” The value effect has gone through some iterations since Benjamin Graham and David Dodd bestowed their masterpiece “Security Analysis” on the investment world in 1934, but it has largely stood the test of time. It’s not a difficult premise to grasp: buying stocks whose price is relatively cheap when compared to certain fundamental valuation measures – like book value, cash flow or net earnings – is on average a better long term investment approach than favoring the more expensive stocks that get red-hot and then flame out just as quickly.

Anomaly, or New Normal?

So far in 2017, value investors are taking cold comfort in the time-tested wisdom of their philosophy. The Russell 3000 Value index, a broad-market measure of value stocks, is up 2.50 percent for the year to date. Its counterpart, the Russell 3000 Growth index, is up a whopping 13.68 percent. That is the kind of performance gap that will make the most lackadaisical of investors do a double-take when their quarterly statements show up in the mail. And their value fund managers are reliving the nightmare that was the late 1990s, when ticky-tack dot-coms regularly crushed “old economy” stocks and made instant (if very short-lived) experts out of amateur punters the nation over.

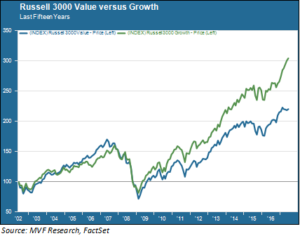

Now, we all know that it is inadvisable to draw larger conclusions from a relatively small time window. But the value effect’s failure to stick the landing extends much further than the current market environment. The chart below shows the relative performance of these same two Russell value and growth indexes over the past fifteen years.

These fifteen years encompass multiple market cycles, from the depths of the dot-com crash to the commodity boom cycle of the mid-2000s, then the 2008 market crash and subsequent recovery (which itself contains at least three sub-cycles). As the chart shows, investors who stuck with a growth discipline performed substantially better than their value counterparts over the course of this period.

The Fleetingness of Factors

Is the value effect dead? Or is it “just resting,” like the Norwegian blue parrot in the Monty Python sketch? When we look at the long-term durability of factors, we tend to follow the methodology of prior generations in using a 30 year window of analysis. When Eugene Fama and Kenneth French (then at the University of Chicago) produced their groundbreaking analysis in 1992 of the value effect and the small cap effect (“The Cross Section of Expected Stock Returns”, published in the Journal of Finance), 30 years was the duration of their time series. Fama and French concluded that both value (defined as low market-to-book value) and small market capitalization were long-term outperformers relative to the broad market.

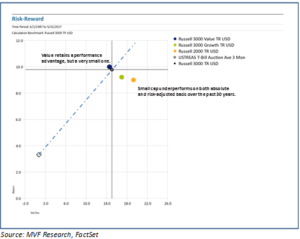

Looking back 30 years from today, value still retains a small edge over growth, while small cap appears to have lost the performance edge that Fama and French reported. The chart below shows the performance of the Russell 3000 Value and Growth, along with the Russell 2000 Small Cap index, over this 30 year period from 1987 to the present.

Value stocks (the blue dot just up and to the left of the broad market benchmark) returned 9.99 percent per annum on average over this 30 year period, which amounts to 0.21 percent more than the broad market. Now, 21 basis points per annum is nothing to sneeze at, particularly as it came with slightly less volatility. But, as the earlier 15 year performance chart showed, growth stocks have outperformed consistently over virtually the entirety of the period from 2009 to the present. The 1992 insights of Fama and French do appear to have diluted somewhat over time.

It’s too early to pronounce the value effect as dead. But factors – even the most durable ones – are never a guaranteed win. Today’s investors on the receiving end of pitches by “smart beta” managers – those sexy factor-based approaches that are currently all the rage – should always remember what is in our opinion the only investment mantra worth its salt: “there is no such thing as a free lunch.”