It’s that most wonderful time of the year…for pundits eager to tell us What It All Meant over the past twelve months. This year has the added bonus feature of being the end of a decade. Hard to believe, but the Tenacious (or Tumultuous, or just plain Terrific/Terrible, take your pick) Teens are coming to a close and we’re about to enter the Twenties for the first time since Scott and Zelda (Fitzgerald) gulped bathtub gin and danced in the Plaza Hotel fountain. What does the decade have in store? There is no shortage of opinions among the financial chattering class. We’ll take this opportunity to weigh in on some of the structural features in place that may or may not be challenging to traditional asset classes as the new decade gets underway.

Decomposing Prices

Bond prices are relatively simple equations: if you know the inputs of coupon, market rate and time to maturity then figuring out the price is just a set of taps into your calculator. Stock prices do not work like that. But there are ways to decompose stock prices into their constituent parts. Doing so can help you understand what drives stock price trends over a long period of time – like, say, a calendar decade.

An investor’s total return on a stock investment is simply dividends received plus (or minus) capital appreciation. Dividends are fairly straightforward. The average annual dividend yield on stocks in the S&P 500 is around two percent and is not likely to vary much from that level for the foreseeable future. No mystery there.

Capital appreciation is the joker in the deck. It requires some measurement tools, none of which are perfect. But the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is one of the most common ways to understand the drivers of price trends, and it can be a useful diagnostic tool if the measurement period is long enough. It’s a simple enough formula: the price per share at a single point in time divided by the earnings per share for the most recent financial reporting period (earnings are typically reported on a quarterly basis).

Earnings and the Multiplier

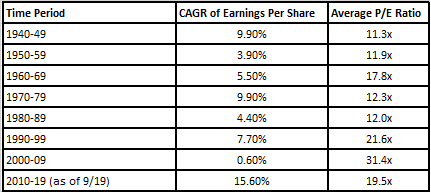

When we look at stock price trends through a P/E ratio prism we are essentially breaking the trend into two component parts. First, there is the earnings growth component. Consider the chart below, which shows the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for S&P 500 earnings per share for each decade since the 1940s. You will see that the most recent two decades have been outliers in terms of average growth.

Source: Robert Shiller Online Database, econ.yale.edu

We also show the P/E ratio for these decades, and here is where it gets tricky. Many analysts look at the P/E ratio as a way to express what an investor is willing to pay for a dollar’s worth of earnings. After all, that is literally what the formula states. Look at the average P/E for the 2010-19 period of 19.5 times. That means that investors over this period paid, on average, $19.50 for every $1.00 of earnings per share in the S&P 500.

But in the previous decade, 2000-09, the P/E was a sky-high 31.4 times – by far the highest level in this entire span of almost eighty years. Were investors really willing to pay that much more for a dollar of earnings in that decade than any time before or since? The answer is no – and here is where we call out the “volatile underbelly” reference in our title above.

The 2000s was a tale of three very unusual events. The first was the peak of the dot-com mania that crested in March 2000. Valuations were in the stratosphere because of the top line, price. Investors really were willing to pay insane multiples of just about anything in the mania that swung into full force in the late 1990s. But by the end of 2000 there was a different force at play. Corporate earnings were starting to fall drastically as the tech slide took hold. In 2001 S&P 500 earnings fell by 50 percent from January to December. In fact, earnings fell faster than stock prices were falling, and that pushed up the P/E ratio.

That same dynamic was in play during the latter part of the decade. Stock prices collapsed during the Great Recession, but earnings collapsed even more – by 18 percent in 2007 and then a whopping 77 percent in 2008. Again, the mathematics of this had the effect of inflating, not compressing, the P/E ratio. It had nothing to do with investor sentiment, which was pretty miserable by the end of the decade. It had to do with the volatility of both share price movements and earnings playing out in real time.

Lessons for Crystal Ball-Gazers

Here’s why we went through this little exercise. There is quite a bit of discussion in the financial press this week postulating that the 2020s will be a very challenging decade for historical-type returns on traditional asset classes. One of the arguments being made is that companies will have a hard time matching the earnings growth they enjoyed in the 2010s. At the same time the prevailing P/E ratio levels, while not at historic highs, are elevated enough to be considered more on the expensive side than on the cheap side. There is not much room for P/E multiple expansion, in other words, nor should we expect to repeat that impressive 15.6 percent average annual growth rate.

Again, though, the story is much more complicated than that. That growth rate looks impressive in part because of where it began – at the end of 2009 when earnings were still coming off the deep lows to which they had fallen in the recession. Apart from that gangbusters first year, the earnings growth trend of this decade has not been all that conspicuously different from past decades. Even so, there is a reasonable case to make that robust earnings growth will be difficult in the late stages of an economic growth cycle when demand typically softens and businesses start to reduce output.

But the more interesting part of the story has to do with the P/E multiple. Yes, it is currently high by historical standards. At the same time, though, interest rates are at historically low levels. Traditional fixed income investors, including pension funds and insurance companies, have been pushed into the equity market because the income stream obtainable from the bond market has been insufficient to meet their spending requirements, such as funding their pensions or paying out claims.

With this in mind, what we may be seeing in equity market multiples is a case of supply and demand. Higher demand for blue chip equities (from these institutional investor profiles) will, all else being equal, raise the selling price level of said equities – no different than any other form of economic exchange. If this is really what is going on, and if the trend of vanishingly low interest rates continues for the foreseeable future, then it is plausible that P/E multiples may remain structurally higher. Under this scenario one would not expect to see a reversion to the levels of 11 and 12 times earnings typical of earlier decades, as shown in the little table above.

We certainly do not have all the answers to this complex puzzle, but it is one we think will be important in helping shape our thought process around the market environment that awaits us in the coming decade. You can expect to hear quite a bit more about it in forthcoming commentary, starting with our annual outlook that will come out in January.