At the tail end of another week of market mayhem, we are going to pick up with the very last point we made in our commentary last week: this is a cycle, not a crisis. We do not have systemically critical financial institutions teetering on the edge of insolvency. We do not have self-described “safe haven” asset classes (like the auction rate notes of 2008) freezing up and leaving investors holding non-tradable paper. Those are the signs of a full-blown financial crisis, and they are not present today.

Closing the Gap

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the current economic cycle is a trickier beast than those of recent decades. The 2020 pandemic, and the massive amount of fiscal stimulus and monetary liquidity provided to combat it, had the effect of creating both red-hot demand and widespread supply chain malfunctions at the same time, setting the stage for the inflation that has persisted throughout 2022.

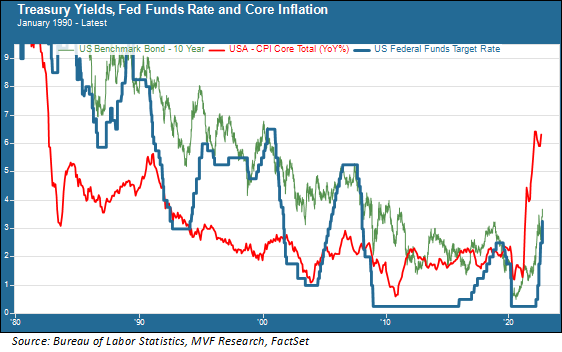

The Fed, along with other central banks, misread the stickiness of this inflationary cycle (in fairness, they had not factored in with sufficient lead time the war in Ukraine and China’s zero tolerance lockdowns, which made a bad situation worse). They found themselves behind the curve in their initial policy responses this year. But more recently, and particularly in the past several months, they have been closing the gap. As the chart below shows, the magnitude of increases in the Fed funds rate (the blue line in the chart) since June have outpaced the more incremental moves of the last several cycles, and at least a couple more outsize moves are expected before the end of the year.

The Fed funds target rate is now in the range of 3.0 to 3.25 percent. Indications provided by the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) at this week’s meeting suggests that the Fed funds rate will eventually settle somewhere just north or just south of five percent, which would bring it much more in line with the high points of previous cycles in the 1990s and early 2000s, and far away from the abnormally low environment of the 2010s. The magnitude of this increase, from the rock-bottom floor of zero to 0.25 percent where the Fed funds rate sat for all of last year and most of 2020, would be the largest since the Volcker Fed increases of the early 1980s. Necessarily, as Fed chair Powell made clear at Wednesday’s FOMC press conference, closing the gap sufficiently to tame this inflation cycle will involve pain, in the form of higher unemployment and meaningfully lower growth. A recession sometime in 2023 is a likely outcome of this policy.

More Pain Now For Less Pain Later

Should the Fed have done more sooner? One can certainly make a good argument that the 0.25 percent Fed funds increase in March this year, coming as it did after Russia had already invaded Ukraine, was inadequate to the task at hand. It has been an evolutionary process for Jay Powell. The good news is that the Fed chair has evolved and adapted to the reality of the circumstances, rather than remaining ideologically wedded to a set of prior convictions. At the Wednesday FOMC briefing he laid out this reality in very clear terms: if we do not get inflation down now, with the full arsenal of monetary tools the central bank possesses, then the economy will not be good for anyone for a very long time to come.

The short-term movements in the equity market since the FOMC briefing have been decisively to the downside. This is reflective of the market’s myopic, unquenchable desire for a “pivot” – for the reflexive liquidity moves to put a floor under stock prices that have been a hallmark of every central banker since Alan Greenspan. It was an amusing moment during the press conference on Wednesday when a reporter from CNBC kept pressing Powell to say something – anything – about a pause in the rate hike program. Just one puckish reporter repeating the word “pause” several times caused the AI-powered trading programs to unleash their buy-signal Krakens, immediately driving the S&P 500 up some 50 points (Jay Powell successfully brushed back the reporter, and prices went back down).

These short-term price movements are backwards-looking, and they blithely ignore the basic fact that the very worst thing the Fed could do at this point would be to blink and pivot to easy money to fend off a recession. That’s what Arthur Burns did in the mid-1970s and it was a conspicuous failure. If the Powell Fed can stay the course until there is sufficient, decisive evidence that inflation has been brought back under control, then there will likely not be the need for the draconian double digit moves Paul Volcker had to make to restore the credibility lost under Burns and his successor William Miller.

There are risks, to be sure. But to repeat what we said above, this is a cycle, not a crisis. As a down cycle plays itself out, the key for any long-term investor is to look forward, not backward.