In what has become an increasingly event-driven year for capital markets, Monday looms large on the calendar with the expected announcement of China’s third quarter GDP growth. Given China’s front-and-center role in the recent stock market correction, investors will want to see what the data say about how things are really faring. Not that the data will necessarily tell them much. The longstanding debate over the extent to which China manipulates its headline data continues apace, with the spectrum of opinion ranging from “a bit” to “entirely.” To grasp what is going on in the Middle Kingdom requires a careful focus on the likely source of whatever growth is in store: the Chinese consumer.

How We Got Here

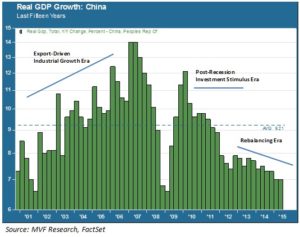

For an understanding of how central the Chinese consumer is to the growth equation – and by extension to what may be in store for global asset markets in the coming months – it is worth a brief visit back to the path of China’s rise to economic stardom. The chart below shows the country’s real GDP growth for the past fifteen years, encompassing its meteoric rise in the early-mid 2000s, the market crash and Great Recession, and the post-recession recovery.

Weekly_Market_Flash_11-13-15_MVCM_2015_0089

There are three distinct economic stories to tell over this fifteen year span of time. While the Chinese economy was kicking into gear in the 1990s, it was really in the first decade of this century that we saw it rise to become the preeminent supplier of all manner of goods to the rest of the world. Demand in key developed export markets in Europe and North America recovered after the 2001 recession. China’s growth trajectory was largely export-driven, with soaring industrial production and equally soaring imports of energy and industrial commodities.

The Great Recession of 2007-09 brought an end to those good times, but only briefly. With cooling demand in its major export markets China turned inward, commencing a massive, debt-fueled stimulus program in late 2008 that continued through the early years of the present decade. Construction and investment, focused primarily on property development and infrastructure projects, drove this second wave of growth. Even while the rest of the world struggled with low-to mid-single digit growth, China continued to grow at or close to ten percent during these years. But consumer spending lagged, accounting for an unusually low 35 percent of GDP as compared to 70 percent in the US and more than 60 percent in most European economies. Eventually the investment boom ran into the headwinds of oversupply. Visitors to China are rife with anecdotal tales of sprawling, eerily unoccupied commercial and residential real estate projects. As investment waned, China’s policy leaders explicitly acknowledged the need to rebalance the economy away from its traditional growth drivers towards something else. Enter the consumer.

Let a Billion Consumers Bloom

Stimulating domestic consumption has thus been a top priority for the government of Xi Jinping ever since coming to office in 2012. What do the results to date tell us? Well, the news headlines over the past several months, not to mention the ham-handed debacle of the government’s trying to control the stock market’s rise and fall and the subsequent devaluing of the currency, would seem to indicate that all is not well. But there are some indications that consumer activity is perking up rather nicely.

Overall retail sales are up more than ten percent this year – faster than the economy overall. Key consumer sectors like furniture and home electronics are up more than fifteen percent. Yes – again, one has to handle published China economic data with some skepticism. But there are enough positive appraisals from those close to the country’s consumer markets to give some support to the numbers. Recall Apple CEO Tim Cook’s sanguine appraisal about his own company’s China prospects amid the panic of the late August market selloff. Nike’s China sales grew by 27 percent in the most recent quarter – the strongest market in a very strong quarter for the company.

We are certainly not Pollyannas when it comes to China. There is plenty that could go wrong with its ambitious rebalancing plan, not the least of which is the massive debt overhang that looms over the economy. China’s debt to GDP ratio, already high, grew by more than 80 percent from 2007-14 according to a study by consulting firm McKinsey. And China’s rebalancing has other implications elsewhere in the world. For one, stocking the shelves of department stores and supplying trendy apps and gadgets to discerning young Chinese technophiles will not replace an import base weakened by declining demand for aluminum, zinc and nickel ore. That’s bad news for resource exporters like Brazil, Russia and Australia.

Nonetheless, we do believe the whirlwind of panic that sprung up in August was overblown. We will study Monday’s GDP numbers carefully, but are much more interested in how these consumer trends will continue to fare in the coming weeks and months. So far, two cheers. Let’s hope for three.