The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting this week came and went without much ado. The 25 basis point rate hike was fully expected, the assessment of economic risks remained “balanced” (Fed-speak for “nothing to write home about”) and the dot plots continued to suggest a total of four rate hikes in 2018 and three more in 2019 (though the market has not yet come around to full agreement on that view). A small spate of late selling seemed more technical than anything else, and on Thursday the S&P 500 resumed its customary winning ways. All quiet on the market front, or so it would seem. We will take this opportunity to call up some words we wrote way back in January of this year, in our Annual Outlook:

“Farmers know how to sense an approaching storm: the rustle of leaves, slight changes in the sky’s color. In the capital marketplace, those rustling leaves are likely to be found in the bond market, from which a broader asset repricing potentially springs forth. Pay attention to bonds in 2018.”

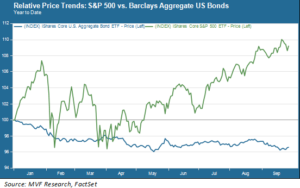

That “rustle of leaves” may take the pictorial form of a gentle, but steady, downward drift.

Nine months later, we have a somewhat better sense as to how this year’s tentative weakness in the bond market may spill over into bigger problems for a wider swath of asset classes. It calls into one’s head a phrase little used since the 1970s: wage-price spiral. There’s a plausible path to this outcome. It will require some careful attention to fixed income portfolios heading into 2019.

What’s Wrong With Being Confident?

The path to a wage-price spiral event starts with a couple pieces of what, on the face of things, should normally be good news. Both consumer confidence and business confidence – as measured by various “sentiment” indicators – are higher than they have been at any time since the clock struck January 1, 2000. In fact sentiment among small business owners is higher by some measures than it ever has been since people started measuring these things. Now, monthly jobs numbers have been strong almost without exception for many years now, but the one number that has not kept pace with the others is hourly wages. That seems to be changing. The monthly cadence was 2.5 percent (year-on-year growth) for the longest time, but now has quietly ticked up closer to 2.8 – 2.9 percent. The evidence for this cadence breaking out sharply on the upside is thus far anecdotal, seen in various business surveys rather than hard monthly numbers, but if current overall labor market patterns continue, we will not be surprised to see those hourly wage growth figures comfortably on the other side of 3 percent by, say, Q1 of next year.

Enter the Trade War

The other side of the wage-price formula – consumer prices – is already starting to feel the effects of the successive rounds of tariffs that show no signs of abating as trade war rhetoric ascends to a new level. Tariffs make imports more expensive. While the earlier rounds focused more on intermediate and industrial products, the expansion of tariffs to include just about everything shipped out of China for our shores invariably means that traditional consumer goods like electronics, clothes and toys are very much in the mix now.

What retailers will try to do is to pass on the higher cost of imports to end consumers. And here’s the rub – if consumers are those same workers whose paychecks are getting fatter from the hot labor market, then their willingness to pay more at the retail check-out will be commensurately higher. Presto! – wage price inflation, last seen under a disco ball, grooving out to Donna Summer in 1979.

Four Plus Four Equals Uncertainty

Recall that the Fed is projecting four rate hikes this year (i.e. the three already in the books plus one in December) and then three more next year as a baseline outlook. A sharp uptrend in inflation, the visible measure of a wage-price spiral, would conceivably tilt the 2019 rate case to four, or perhaps even more, increases to the Fed funds target rate. Right now the markets don’t even buy into the assumption of three hikes next year, although Eurodollar futures spreads are trending in that direction. That gentle downward drift in the bond market we illustrated in the chart above could turn into something far worse.

Moreover, the wage-price outcome would very likely have the additional effect of steepening the yield curve, as increased inflationary expectations push up intermediate and long term yields. Normally safe, long-duration fixed income exposures will look very unpleasant on portfolio statements in this scenario.

The wage-price spiral outcome, we should remind our readers, is just one possible scenario for the months ahead. But we see the factors that could produce this inflationary trend as already present, if not yet fully baked into macro data points. From a portfolio management standpoint, the near-term priorities for dealing with this scenario are: diversification of low-volatility exposures, and diversification of yield sources. Think in terms of alternative hedging strategies and yield-bearing securities that tend to exhibit low correlation with traditional credit instruments. These will be very much in focus as we start the allocation planning process for 2019.