If you were following the flow of economic data releases this week you probably took note of the Consumer Price Index release on Tuesday, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPI, of course, has been the talk of the town within the last year as inflation has soared to levels not seen since the early 1980s. And this month was no exception; the March headline CPI, including those volatile categories of energy and food items, jumped by 8.6 percent compared to March 2021 – a new 40-year record.

You may have also noticed that stocks rose quite briskly on Tuesday, and if you tuned into what the talking heads were chattering about on CNBC you would have heard the phrase “peak inflation” over and over again. Financial news groupthink being what it is, it didn’t take too long for “peak inflation” to morph into “peak Fed” and suddenly it might have seemed like all the problems we’ve been dealing with so far this year are about to go away. Right? Or is it not that simple?

Points of Comparison

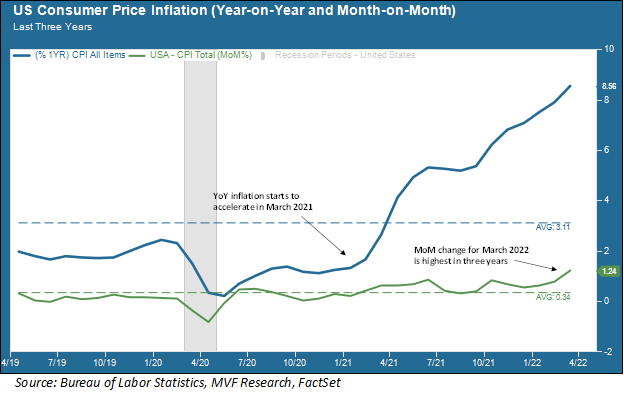

The chart below shows the change in the Consume Price Index over the last three years. We present two ways of looking at inflation: how much it has changed from twelve months ago to today (called year-on-year or YoY), and how much it changes from one month to the next (month-on-month or, quaintly, MoM).

The first thing we want to focus on here is the year-on-year number (in blue), because that is what all the pundits are looking at when they talk about “peak inflation.” As you can see from the chart, year-on-year inflation started to really pick up about a year ago, and it’s been mostly a straight line up since then. Why is that important? Because when we say that the headline YoY CPI number in March 2022 is 8.56 percent, what we mean is that is how much prices have gone up since March 2021. When the BLS reports the April number next month (May 11, if you want to make a note on your calendar) the point of comparison will be April 2021, and so on. The point of comparison, in other words, will increasingly be reflecting that accelerating inflation trend from the prior year – so the percentage gain should be more modest. “Year-on-year headline inflation should not be trending above 8.6 percent in the coming months” is, therefore, what the big story was on Tuesday and why it seemed to have a positive effect on investor sentiment.

MoM Has a Say

But that’s not the entire story. For that matter, it’s not even the most important story from the standpoint of consumers dealing with the practical effects of inflation in their own lives. For that story let’s look at the other number on the above chart – the month-on-month price change (the green line). What that line shows is that prices in March, on average, were 1.24 percent higher than they were in February. That, in turn, is the most that prices have risen in one single month over the last three years. Now, this being the headline inflation number, the big drivers of the MoM increase were food and energy. March, you will recall, was the first month to feel the added shock on energy prices coming from the war in Ukraine.

This number is likely to fluctuate in the months ahead, because food and energy prices in general are more volatile than other categories of consumer goods (which in turn is why many economists prefer to look at the core inflation number, which excludes these categories, for analyzing longer-term inflation trends). But it is much less likely for anyone to confidently assert that the MoM trend has peaked. We simply don’t know. There are likely to be ongoing pressures on both food and energy as long as the war continues (which, sadly, is likely to be for a while). The Covid lockdown in Shanghai has closed one of the world’s busiest ports and thus thrown yet another wrench in the troubled global supply chain network. Consumer demand in the US still appears to be strong, though expectations of higher prices may be starting to have a more pronounced effect on household budgets.

The point is that, while it is certainly good to have one measure of inflation looking like it has peaked, that does not give any kind of “all-clear” signal. Nor does it mean that the Fed can relax, kick back and buy more bonds to goose asset prices (which at the end of the day is what investors want more than anything). Expectations remain that the Fed will be raising rates by 0.5 percent when the FOMC meets next month. Yes, the supply chain problems and the other forces driving prices higher will eventually work themselves out. But there is still a ways to go.