Some of the things that define life in the financial markets and economy of 2022 have their origin story forty years ago, in 1982. Consider this: the stock buyback, one of the perennial bull factors by which stock prices keep on keeping on, was illegal before 1982. In that year an obscure provision in the SEC code called Rule 10B-18 was enacted that allowed corporations to avoid charges of stock price manipulation through buying back their own shares. The original intention of the provision was to protect companies from corporate raiders (this was also the colorful era of the likes of T. Boone Pickens and young-ish Carl Icahn). It didn’t really accomplish that, but it sure made future generations of stock market bulls happy.

Another shiny new thing that came along in 1982 was the introduction of financial futures for trading on commodities exchanges. Once the redoubt of broad-shouldered Midwestern types dealing in pork bellies and soybeans, venues like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange were now open for trading in yen futures and options on S&P 500 futures. A whole category of investments whose value derived from that of other assets – derivatives, in other words – was born and in many instances would go on to be more widely traded than the underlying assets themselves.

The Age of Volcker

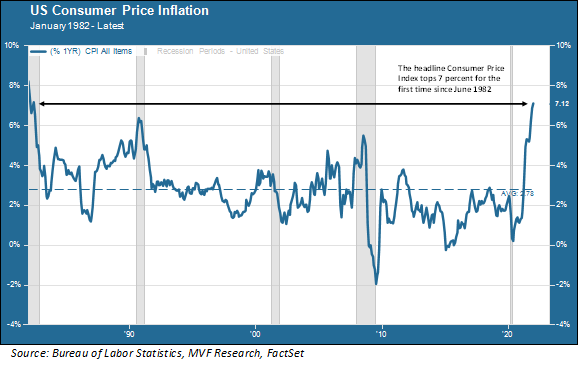

1982 was also the last time headline inflation in the US was over seven percent…until this week.

As the above chart shows, inflation in June 1982 was on its way down from much higher levels a couple years before that. These were the final months of the Age of Volcker – Fed chairman Paul Volcker had deliberately forced interest rates up to historically high levels in order to bring inflation, the scourge of the 1970s, back down to earth. As you can see in the chart, Volcker succeeded admirably. The Consumer Price Index and other measures of inflation largely stayed within low to mid single digits for the entirety of successive cycles of economic growth and decline up to the present. Now a different Fed chair, Jay Powell, has a different inflation challenge on his hands. How does he stop inflation from going higher than it is today, without resorting to the draconian measures Volcker used to tame it in the early 1980s?

Four for Four?

This week we heard from four different Fed members – two regional presidents and two Fed Board of Governors members including Lael Brainard, Biden’s pick for the Board’s Vice Chairperson – about the absolute primacy of fighting inflation. It’s job number one for the central bank. To that end, all four members expressed openness to the possibility of at least three, maybe four or even five, rate hikes in 2022. This is quite extraordinary when you consider that just one year ago the bank was ruling out even one rate hike in 2022 and maybe not even one for 2023. How times have changed.

Markets are not entirely sure what to make of this newfound inflation-fighting resolve, which is evident in the way stocks have lurched back and forth in volatile trading for much of this week. On the one hand the Fed’s determination is seen as a positive, because if they can credibly be seen to be fighting inflation with success, then we are less likely to see an organic, bottom-up increase in inflationary expectations from households and businesses. That should be positive for longer-term economic growth.

On the other hand, higher interest rates – yikes! Markets are so used to the low interest rates – along with two major programs of asset purchases by the Fed – of the past decade that the prospect of monetary tightening is unsettling. Unsurprisingly, the pockets of the market feeling the chill most intensely are the riskier areas; companies with high uncertainty around future earnings and cash flows. Higher interest rates make those putative future cash flows less valuable in present-day terms. That in turn explains why around 40 percent of the 3,000 companies on the Nasdaq exchange, a popular listing venue for growth-oriented technology companies, are trading around half their peak value in the past twelve months.

Not Paul Volcker’s Inflation

The other variable that lends uncertainty to the current environment is that the inflation we are seeing today is not the same as it was in the late 1970s. There is both a demand side and a supply side to today’s inflation: the former from the vast amounts of relief and stimulus money that flooded into the economy in 2020-21, and the latter from the many disruptions that continue to beset global supply chains. Raising interest rates can be effective in taming domestic demand; it is less directly useful in solving supply chain problems, many of which are very local to critical hubs in China, Vietnam and elsewhere.

In 1974 the administration of then-President Gerald Ford came up with a campaign called WIN – Whip Inflation Now – in an effort to build support for inflation-fighting measures and lower inflationary expectations. The campaign was a bust, inflation did not get whipped in any fashion, and Ford was out of a job after the elections in 1976. Inflation was no kinder to his successor Jimmy Carter, another one-term president. Not just investors, but many among the current governing party in Washington, DC are hoping that Jay Powell and his inflation-fighting Fed have what it takes this time around.