Going into the Federal Open Market Committee meeting this week, the over-under was a bit tighter than usual. In the previous meeting in early May, Fed chair Powell had telegraphed pretty convincingly that the Committee was likely to pause in the June meeting. Since then, though, a flurry of Fedspeak – along with more robust job numbers and still-high core inflation – suggested that another increase might be in the works. In the end, the kibbitzing settled around a consensus view that the Fed would “skip” rather than “pause,” with no rate hike in June but a final 0.25 percent increase in July to bring this eighteen-month monetary tightening program to an end.

One More for Good Measure

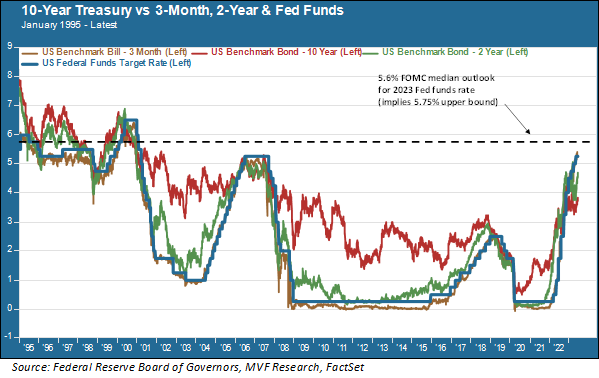

In the end, though, the FOMC had a surprise in store for the market. The Summary Economic Projections, a representation of where Committee members think that certain macroeconomic metrics and interest rates will be in the next several years, showed the median projected Fed funds rate for 2023 to be 5.6 percent. That implies another two – not one – rate hikes, with a final Fed funds range of 5.5 – 5.75 percent (up from the current range of 5.0 – 5.5 percent). If the SEP assumptions become reality (they are only nonbinding estimates at this point), it will represent the highest level for the central bank’s key interest rate since January 2001.

Recent economic data suggest two concurrent trends that may explain the reasoning behind the additional rate hike assumed by the SEP. The labor market is still running hot, a full year and a half since the first rate hike in March 2022. The maximum unemployment rate is projected to be 4.5 percent, lower than the May assumption of 4.6 percent. On the flip side, the SEP assumptions for core inflation are higher than they were in May. In fact, core inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index has been on an elevated plateau for the duration of this year so far, with a month-on-month gain of 0.4 percent each and every month except February, when it was 0.5 percent. The month-on-month trend at this point is a more important yardstick for the Fed than the year-on-year comparisons. It remains elevated due largely to the stickiness of core categories like shelter, vehicles and transportation services. At the post-FOMC press conference Powell expressed his view that these are likely to continue being more stubborn. Meanwhile, he was more upbeat about the potential for that fabled “soft landing” thanks to the continued strength of the jobs market. Hence the case for that second additional rate hike.

The Bond Market Shrugged

As the above chart shows, the current level of Treasury yields across the spectrum of maturities remains well below the final level implied by the SEP. Intermediate rates, indeed, are positioned well below even where the Fed funds rate is today, let alone where Committee members think it will wind up. This, as the chart clearly shows, is not the historical norm. In all but a small number of time periods, interest rates follow an upward-sloping curve from the shortest to the longest maturities. In the past, when this shape has inverted, it has in most cases been the precursor to a recession.

The inverted yield curve today is one of the longest on record – and we still do not know for sure if it is going to actually prefigure a recession (though that assumption, which we first articulated in our outlook at the beginning of this year, is still in our base case model). One might have thought that the Fed’s SEP surprise this week would have had an immediate effect on interest rates, representing as it does a repricing from current levels. But one would have been wrong. Rates are more or less where they were a week ago, with just a little more movement in the 2-year and the 5-year Treasuries than in the 10-year.

As has often been the case this year, the bond investor is left with a dilemma. Lock in the highest nominal yields in the past 15 years, and assume that inflation-adjusted purchasing power will turn positive sooner or later? Or conclude that the bond market, dripping with recency bias, is still not listening to the Fed, still thinks that a rate-cut unicorn is just around the corner, and is about to get whacked with a stiff dose of reality that sends rates sharply higher? It’s a dilemma without a clear answer (which, we suppose, is what makes it a dilemma in the first place). In our portfolios, bonds serve the dual purpose of safety and yield. The mix of those two objectives will change with the specific financial goals of each client, and that client-specific mix will inform how we respond to the dilemma.