As 2014 comes to an end we naturally ponder the year that was and the trends that shaped the investment narrative. There are plenty of contenders for story of the year honors, from the plunge in energy prices to the return of geopolitics and the soaring U.S. dollar. We would argue, though, that interest rates were, are, and will continue to be a driving force in their impact on a broad spectrum of asset classes. In this post we consider how rates confounded expectations over the past twelve months, and how they did not.

Duration Conundrum

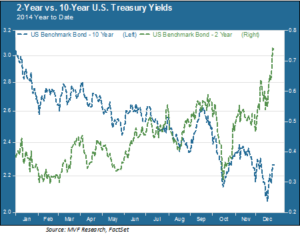

“Rates will go up in 2014” gelled into the collective mindset of Wall Street in the wake of the Fed’s December 2013 announcement that it would begin tapering its QE3 bond buying program. Bond managers of all stripes set shorter duration targets, expecting that yields on intermediate and long term issues could soar. Indeed, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield had jumped more than 1.25% in a torrid run from May to September, supplying a real-world case study to support the short duration bet. But as it turned out, the bet backfired. As the chart below shows, short term yields (represented here by the 2-year Treasury note) did rise – substantially – in 2014. But the price of the 10-year Treasury rallied, and its yield fell from more than 3% to just above 2% in early December.

The World Is Flat

The above chart serves as a useful reminder that interest rate theory and the real world don’t always coincide. Specifically, duration strategies need to take into account, not just the potential direction of rates but also the shape of the yield curve. The curve flattened in 2014 as short term rates rose while longer term rates fell. The divergence was most pronounced on two occasions; first, during May and June when the 2-year rallied sharply while the 10-year drifted lower; and, second, in the aftermath of the mid-October equity markets pullback when short term rates soared while the 10-year yield fell to its lowest year to date level. As it turned out, rate hike expectations did drive yields higher – for shorter term securities that would in any case be more directly affected by a Fed increase. But other supply and demand factors were at play in keeping a lid on intermediate and long term yields.

2% Is The Charm

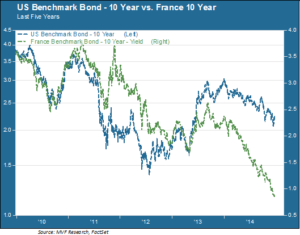

Arguably the most impactful of those other supply and demand factors was the relative appeal of U.S. rates when compared to other developed market sovereigns. 2% seems paltry unless compared with yields in the sub-1% range, where most of Europe and Japan have been this year. Consider the chart below, showing the relative yield trends of the U.S. and French 10-year benchmarks over the past five years.

The negative spread between U.S. and French issues has persisted for well over a year, but it is not typical in the context of longer historical norms. In 2014 it had the effect of supplying the answer to the question on everyone’s mind at the beginning of the year: who will pick up the slack once the Fed stops buying bonds. Foreign buyers more than made up for the reduced demand brought about by tapering. Coupled with periodic haven retreats in the face of geopolitical disruptions, the relative charms of 2% have been enough to keep the 10-year from following the 2-year upwards.

Monitoring Mario

The resilience of European yields is due in no small part to continued expectations that Europe’s dire economic conditions will require a more full-throated QE program from the ECB than has been the case to date. Indeed, we see a more robust Eurozone stimulus program as fairly likely sometime in the first half of 2015. It’s not a given, though, and there are plenty of variables at play that could impede ECB Chairman Mario Draghi from delivering the goods expected by the market. A sentiment change away from Eurozone QE, and/or perceptions of elevated risk among peripheral sovereigns could bring an end to sub-1% Europe. What the lessons of 2014 teach is that, when it comes to rates, policy and yield we should expect the unexpected. Be prepared for rates to go up in 2015. Be prepared, as well, for alternative scenarios.