For as long as we have been working in the financial industry, which comprises more decades than we care to let on, people have been worrying about debt and deficits. Throughout this time, though, investors the world over, institutional and individual alike, have been reliable buyers of US government debt. Deficit hawks, fretting over irresponsible Washington spending, turned out to be Cassandras endlessly predicting a financial apocalypse that never happened.

But the debt continued to grow, and so did the size of the deficit. In the 1980s the federal deficit was typically somewhere around one to two percent of GDP; today it is above six percent. In 1985, while we were all bopping out to “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” and knocking back Crystal Lite in our leg warmers, the total public debt was about 40 percent of GDP; today, that ratio is near a peacetime high of 120 percent. The conditions have changed, and those beaten-down deficit hawks may be on the cusp of having their told-you-so moment.

A Tale of R and g

In the world of finance, an upper cap R is the symbol for the rate of return, expressed as a yield on an investment, while g (lower cap) signifies the projected long-term growth rate. At the macroeconomic level of national output, these two terms come together in a relationship between the economic rate of growth and the cost of borrowing to obtain that growth, both adjusted for inflation. Long-term solvency is achieved by the rate of growth being higher than the rate of borrowing.

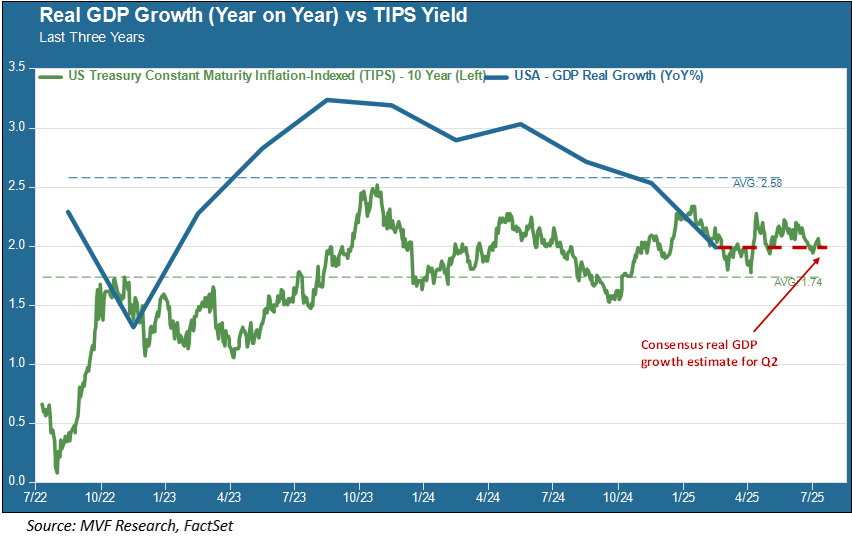

With that in mind, consider the chart below, showing the past three years of real year-on-year US GDP growth versus the yield on 10-year inflation-protected US Treasuries (TIPS).

As the chart shows, the relationship between borrowing costs and growth is extremely close, with inflation-adjusted Treasury yields slightly outpacing real growth rates. In a couple weeks we will get the first reading for third quarter GDP growth, and the current consensus among economists is for growth to be right around the same two percent (year-on-year) level as it was for the second quarter. We show this in the chart with the crimson dotted line.

The Specter of Stagflation

Why is this important? Well, it’s the same as any situation involving debt and income. If you take out a personal loan, your own household finances will be fine as long as (a) you don’t borrow an ungodly sum, and (b) your household income grows at a faster rate than what you pay in interest and principal on the loan every month. If that equation changes – if you lose your job, or your salary flatlines, or you have a variable rate of interest on the loan that suddenly shoots up – then your financial situation is precarious.

Which brings us to the question on everyone’s mind in 2025: what is going to happen to the US economy? If interest rates subside a bit and growth picks up, then the debt situation becomes more manageable. Unfortunately, that does not appear to be the likeliest scenario. The bill that made its way through Congress last week stands to add a substantial amount of debt to the national balance sheet, with an estimated $3.3 trillion addition to the deficit over the next ten years.

Meanwhile, even after backing away from the most outlandish tariffs announced back in April, the average global tariff on goods coming into the US stands at 15 percent, the highest since the Smoot-Hawley tariff era of the 1930s (never a good decade to which to be making economic comparisons). The potential for structurally higher inflation and lower growth – stagflation, in other words – is real, and the probability of this scenario coming to pass is growing by the day.

There are policy prescriptions that could make the stagflation outcome less likely, but we see no evidence of them emerging from the current batch of individuals making economic policy. As for investment portfolios, there is no perfect strategy against stagflation. But it raises the importance, in our view, of a careful and deliberate diversification, across geographies and asset classes for both equities and fixed income. The chips will fall in different ways in different places in the coming months and years. Disciplined asset allocation is about to get a lot trickier, and a lot more important.