MV Weekly Market Flash: A Whole Lot of Nowhere

Read More From MVThree months ago, to the day, we wrote our first post-election commentary entitled “The Markets Are The Guardrails,” the idea being that whatever craziness might be going on elsewhere in the new administration, on the economic front at least their wildest ideas would likely be tempered by the reaction of stock and bond markets, about which these people, to a person, care deeply. So far, we would say that our prognostication back in November has been validated. There is plenty of crazy stuff going on elsewhere, and because our weekly commentary is about economics, not politics, we will leave it...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The AI Story’s Next Chapter

Read More From MVOver the past two years, as advances in artificial intelligence turned into a massive tailwind for the US stock market – carried aloft by a relatively small number of companies with a credible claim to be at the center of the AI story – skeptical observers compared the phenomenon to the Internet boom of the late 1990s. That boom, as anyone around at the time will no doubt recall, ended with a spectacular crash at the turn of the millennium. So long to Pets.com and its ilk, popped into weightless effervescence as the dot-com bubble burst. So too, the AI...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Bond Vigilantes Hold Fire, For Now

Read More From MVThe 1980s was a colorful decade for many reasons, and not just limited to the cultural icons of the day like Boy George or Max Headroom. The economic arena had its own personalities. There was Michael Milken, the swaggering Drexel Burnham Lambert bond trader perched at his X-shaped desk in Beverly Hills, king of the junk bond market. And Ivan Boesky, merger arbitrageur extraordinaire and coiner of the “greed is good” mantra later immortalized by his fictitious avatar Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie “Wall Street” (by which time Boesky himself was cooling his heels in the Lompoc Federal Correction...

Read More2025: The Year Ahead

Read More From 2025:It is never easy to predict what is going to happen in the next twelve months, and very rarely do the best efforts of economists, sociologists and market pundits of all stripes get it all right (you can generally toss away all those specific numbers the big banks and securities firms come up with about where the S&P 500 or Nikkei 225 will be come New Year’s Eve 2025, and they will all be revised multiple times anyway between now and then). It is especially hard this year, because the world is in a profound state of transition. What we...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: China Fast Out of the Gate

Read More From MVThere is a lot going on in China right now. Talk of punitive tariffs against the Middle Kingdom swirled through the halls of Congress during a week of hearings for cabinet nominees. China’s trade surplus with the rest of the world hit an all-time high of $992 billion, probably giving even more grist to the tough-tariff mill. Its population fell by 1.4 million souls, declining for a third year in a row. Though China did, apparently, manage to gain several hundred thousand-odd virtual humans as TikTok aficionados the world over, in a fit of pique over the potential loss of...

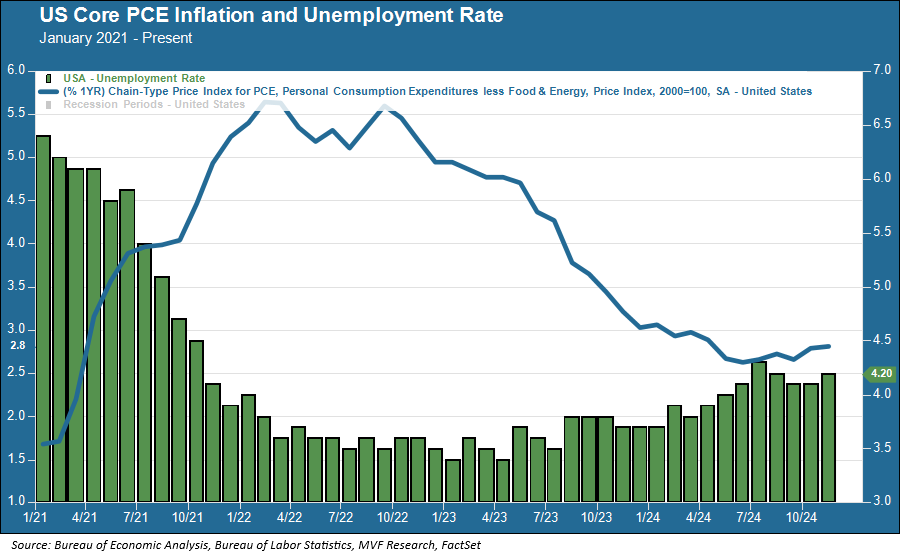

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Hot Jobs, Cold Fed

Read More From MVWhat a difference a few months can make. Late last summer, markets were freaking out about what seemed to be a rapidly cooling labor market. Nonfarm payrolls for August increased by just 78,000, well below the 206,000 average for the twelve months prior to that. The Fed, too, was noticing the apparent tapering of conditions in the jobs environment. With inflation seemingly under control, the timing was right for an outsize interest rate cut, which duly arrived in September. That was then. In November, nonfarm payrolls came in with a robust gain of 212,000. Today, we learned from the Bureau...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Four Things On Our Radar

Read More From MVMarkets are trying to find their footing as the year gets underway, so far without much success. The S&P 500 is slightly lower in morning trading today after losing ground in each of the last five trading sessions, stretching back into the December holiday period. No Santa Claus rally this year, kids. But – so far, anyway – nothing too much out of the ordinary for a standard-issue pullback following a furious rally. Stocks rose more or less nonstop after the November election, reaching a peak in early December. Since its last record high on December 6, the S&P 500...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Goodbye to 2024

Read More From MVThe next time we write our weekly column, it will be the third day of 2025 and the beginning of another year of both predictable and completely unfathomable twists and turns. As we prepare to navigate whatever lies around the next bend in the river, let’s look back at the events and forces that have brought us to where we are today. For what feels like the eleventy-millionth time in a row, the market of US large cap stocks, led by growth-oriented sectors in information technology and communications, left just about every other asset class in the dust. The S&P...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Brake Lights Ahead

Read More From MVThe Fed cut interest rates again this week in a widely telegraphed and entirely unsurprising move (though not without one notable dissent from Cleveland Fed head Beth Hammack, who voted to keep the target Fed funds rate at its current level). Somewhat more surprising was the change in projections by members of the Federal Open Market Committee as to the likely cadence of rates in the year ahead. Back in September, the median estimate for 2025 rate cuts was four, which would give us a target Fed funds rate in the range of 3.25 – 3.50 a year from now....

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Vigorous Words, But No Bazooka

Read More From MVBack in September, the financial press called it a “blitz.” On September 24 the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, announced a series of measures to stimulate the moribund Chinese economy. Among the few initiatives mentioned by the PBOC with any specificity was a planned $114 billion fund (a “war chest” in the patois of the military terminology-loving media talking heads on CNBC) to be lent to asset managers and the like to buy shares in domestic Chinese companies, presumably on the notion that animal spirits in equity markets should somehow spill over into feistier household spending on...

Read More