MV Weekly Market Flash: More Treats Than Tricks

Read More From MVIt is supposed to be the month of March that comes in like a lion, out like a lamb, according to the custodians of timeless wisdom. This year, though, that appellation could just as well apply to September. After a volatile beginning, financial markets settled down and more or less calmly navigated the twists and turns of the daily news cycles. At the end of it all, the S&P 500 posted a gain of just over two percent from the beginning to the end of the year’s ninth month – not a shabby chunk of change. So how is the...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Tailwinds of September

Read More From MVAs we noted in one of our commentaries earlier this month, September has a history of bad vibes for equity markets. For a while there, it seemed like this was going to be one of those glass-half-empty years with sagging share prices and lots of volatility. But, as we also observed in that earlier commentary, every September has its own story. In the end, this year has been the story of three tailwinds that combined to take the edge off seasonal negativity and deliver unto us a pleasantly sustainable rally through the second half of the month. The Return of...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: What To Expect When You’re Expecting a Rate Cut

Read More From MVWell, in the end they went big. The Fed cut the Fed funds target rate by 0.50 percent, and for maybe the first time in this entire monetary policy cycle, the bond market got it right (futures markets had priced in about a two-thirds probability of a jumbo cut versus the more usual 0.25 percent increment). The stock market seems to be trying to sort out all manner of mixed emotions – closing down after bouncing around in the immediate wake of the announcement on Wednesday, then staging a rally for the ages yesterday, and back into a bit of...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: China In 3D

Read More From MVDemography, deflation and debt. These are the Three Ds of China’s economic lassitude, and they have all been in the news recently. International investors, meanwhile, continue to add a fourth D to the picture – departure. The Shenzhen A shares index, a bellwether of mainland Chinese equities, is down 32 percent from its 2-year high set in February of last year. And it’s not just portfolio managers with their fleet-of-foot capital heading for the exits; US and European businesses with longstanding foreign direct investment in China are rethinking the dependence of their supply chains on a China that has become...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: September, True to Form

Read More From MVYou may have noticed that markets have been a tad jittery lately. The S&P 500 is down around 2.6 percent from the beginning of the month, and about 2.9 percent off its last record high set on July 16. There are lots of plausible explanations out there in the crossroads and roundabouts of financial media chatter. Uncertainty about the upcoming election, fears of a potential recession, doubts about whether the Fed is moving fast enough on interest rate cuts – all of these and many more fill up the pages of the Wall Street Journal and the talking heads panels...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The De-Inversion Cometh. What Next?

Read More From MVThursday morning opened the same way every morning has opened since July 5, 2022 – with the Treasury yield curve inverted at the 2-year and 10-year maturities. That’s 786 consecutive days (counting weekends and holidays) of an inverted curve, the longest on record by far (the previous record was 624 days in 1978). But on Thursday, the difference between the two maturities was a scant three basis points, or 0.03 percent, suggesting that the end of this magnificent streak is fast approaching. Since an inverted yield curve is supposed to be a reliable harbinger of a recession, enquiring minds want...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: If It’s Late August, It Must Be Jackson Hole

Read More From MVLate August means different things to different people. The last chance for a relaxing week at the beach before the new school year begins. Putting up the college flag on the front lawn in anticipation of the upcoming football season. Endless variations on recipes for those fresh tomatoes, straight from the garden. And for finance nerds like ourselves who closely follow the twists and turns of monetary policy, it’s Jackson Hole time. At their annual gathering in the shadow of the majestic Grand Tetons of Wyoming, the world’s leading central bankers pair cowboy hats with their sober business suits and...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Apocalypse Not

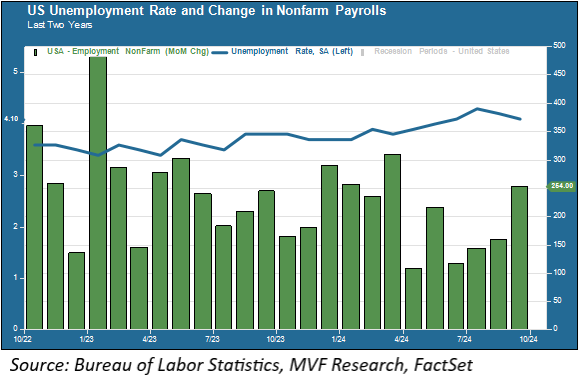

Read More From MVTwo weeks ago to the day, a soft jobs report sent risk asset markets into a tizzy. The report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on August 2 seemed in investors’ minds to validate two data points from earlier that week, one a survey on manufacturing activity and the other a weekly tally of new filings for unemployment, suggesting that the economy was slowing at a faster than expected clip and could be in recession by the end of the year. Bearish sentiment ticked up. Investors bought lots of Japanese yen because that’s one of the things people do when...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Notes From A Weird Week

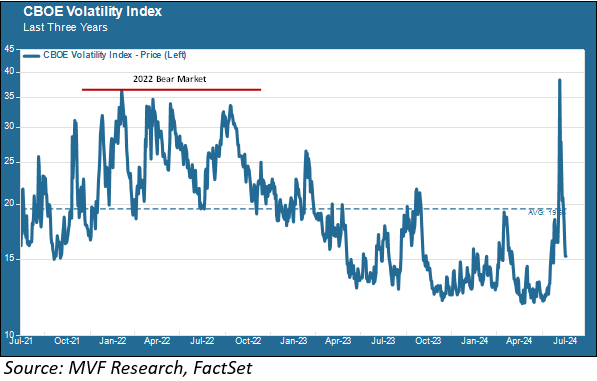

Read More From MVIt’s been a minute, as they say. What to make of it all? Let’s start with that first bit of news to which we all woke up on Monday morning, namely a 12 percent drop in the Nikkei 225 benchmark index of Japanese stocks. That one-day plunge had those of us who were around and following markets in October 1987 reminiscing, and not necessarily in a good way. It’s worth noting that Monday’s percentage loss was twice the magnitude of the six percent drop in the Nikkei immediately following the earthquake in 2011 that produced a meltdown in the Fukushima...

Read MoreMVF Special Update: 08/06/2024

Read More From MVFTo Our Valued Clients: As you are no doubt aware, there has been a considerable amount of volatility in global investment markets over the past several days. While we endeavor to keep you informed about important market developments on a weekly basis every Friday, we thought that the unusual amount of choppiness, along with some at times (in our opinion) overblown chatter in financial media outlets, merited a special comment a few days ahead of our regular Friday commentary. The key point we want to emphasize here it that yesterday’s big pullback, with the S&P 500 declining by 3.0 percent...

Read More