MV Weekly Market Flash: The Chorus of the Bulls

Read More From MVThe latest Global Fund Manager Survey published by the Bank of America is out. The survey canvasses the opinions from 238 institutional fund managers, collectively managing around $364 billion, on a wide spectrum of issues around the economy and financial markets. The tenor is pretty upbeat. Well, very upbeat, actually. The sentiment indicator – a broad measure of expectations about economic growth and equity market performance – is the highest it has been since July 2021. What to Expect When the Market Expects Bulls That sounds nice, perhaps. Fund managers (for reasons we do not entirely share) are happy with...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Europe Finishes Strong

Read More From MVIt has been something of a rite of passage in recent years. As the year gets underway in January, the financial chattering class lands on the age-old question. Is this Europe’s year? Is it time for portfolio managers to shift weights out of the US and into assets on the other side of the Atlantic? Typically, this festival of talking heads will take place immediately after a day in which the MSCI Europe Index or a similar benchmark ends up ahead of the S&P 500. In recent years, though, it has always ended the same way. Whether the out-of-US rotation...

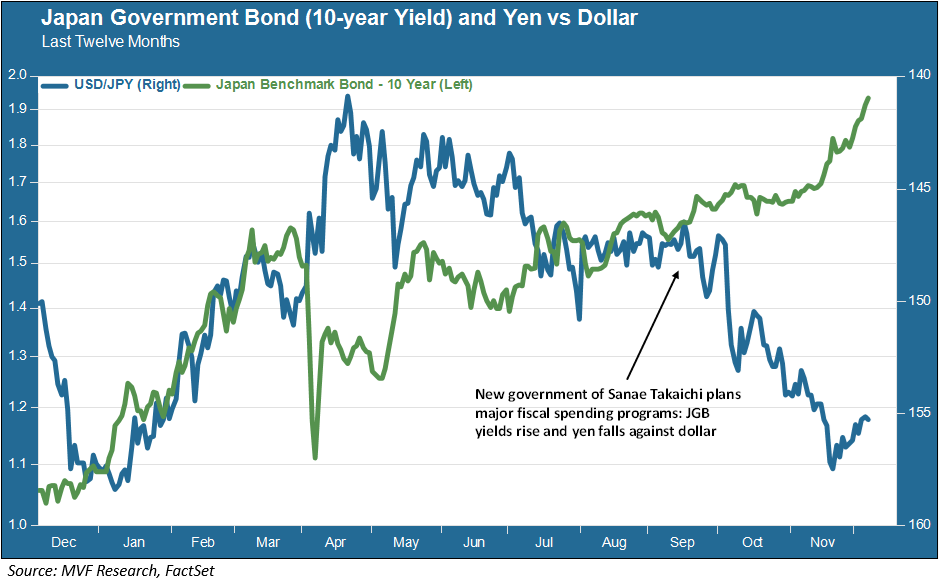

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Japanese Bonds, a 2026 Wild Card

Read More From MVHappy December! It’s the last month of 2025, which has been a strange year in oh so many ways. It is also the month when, by custom and tradition, our leading financial institutions tell us, in very specific terms, how the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq and the Dow will all fare in 2026. Please. You will have just as much insight into what the US stock market will look like twelve months hence if you ask the question of your friendly neighborhood psychic. Or your dog, for that matter. Rather than trying to pin a number on something that...

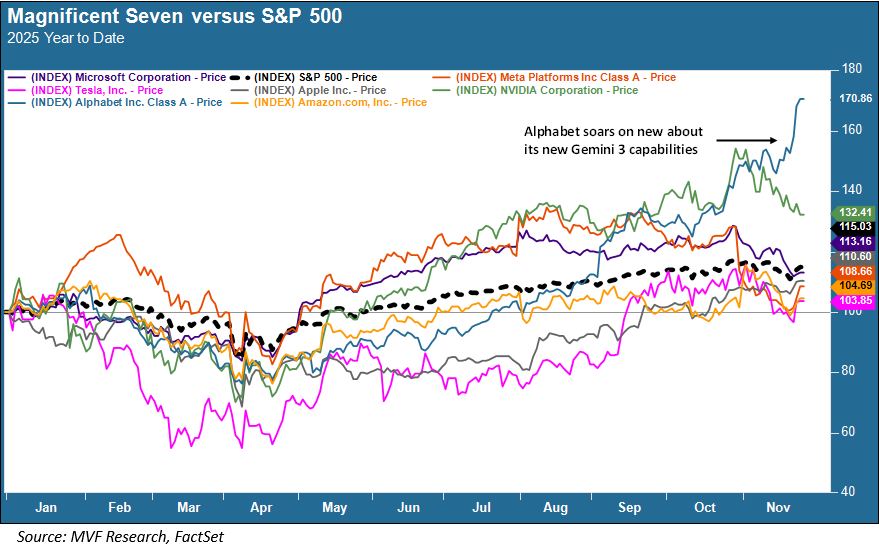

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Incredible Shape-Shifting AI Story

Read More From MVAnd then there were two. Oh how ye have fallen, mighty Magnificent Seven of yore. Today, just two of these august mega-cap companies, so crucial to the long-running saga of AI dominance over the US stock market, are outpacing the S&P 500 in price gains for the year. The fortunate two are Nvidia and, now in the group’s pole position, Alphabet. And herein lies a lesson about how the AI story, through all its strange twists and turns over the past three years, keeps coming out ahead. The Deep Seek Effect, Reborn Earlier this year, the AI world was shaken...

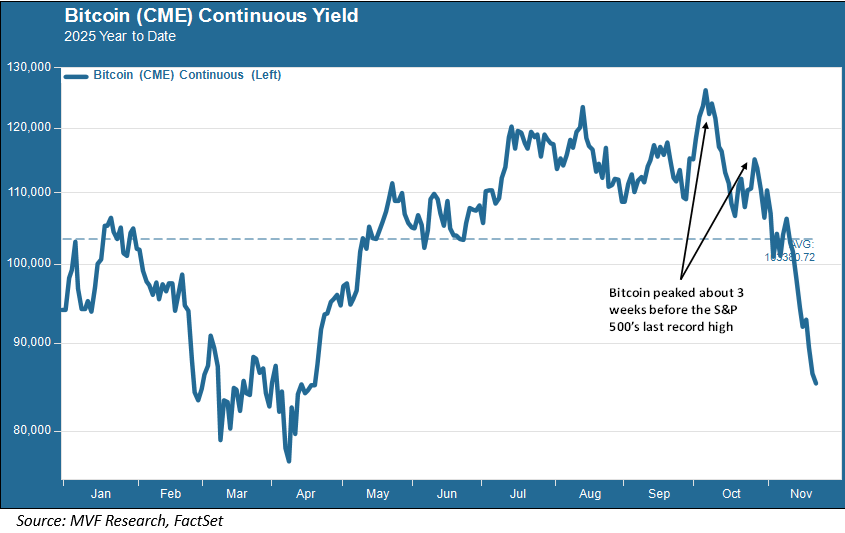

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Bitcoin and the Bear

Read More From MVWe don’t talk much about bitcoin (or other cryptocurrencies) in this space, mostly because this asset class does not have a place in our asset allocation models. Our advice to clients in this regard is simply: treat cryptos like you would treat any purely speculative wager, be it sports betting or the roulette table in Vegas or whatever else. In other words, a discretionary activity to undertake outside the guardrails of your long-term financial portfolio with specific objectives for growth and capital protection. Punters Rise, and Fall Sometimes, though, a discussion about bitcoin is helpful, and this tends to be...

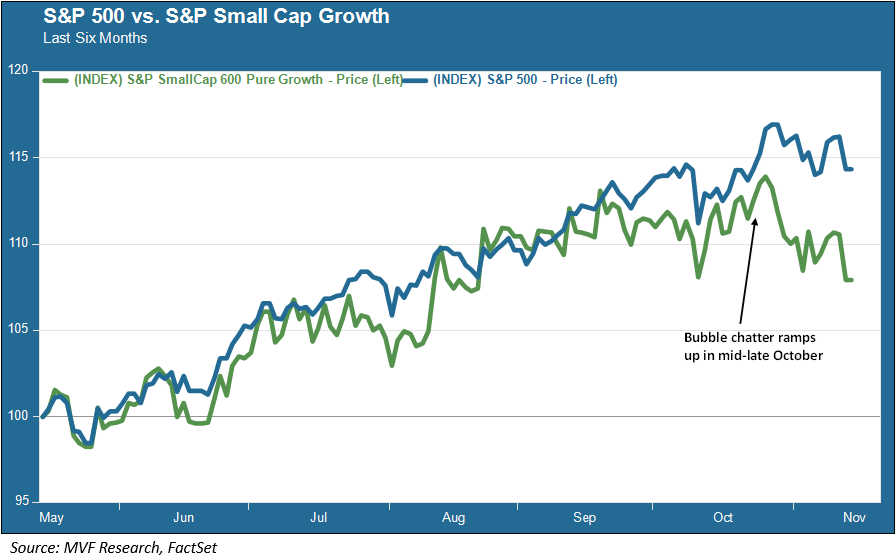

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: What’s Driving the Pullback?

Read More From MVIn the second half of October, the financial chattering class seized onto what seemed like a throwaway comment by OpenAI head Sam Altman during an interview. Responding to a question, Altman acknowledged that the AI space in the stock market was probably in bubble territory, though adding that while the space would probably go through some short-term pain, as generally happens with new technologies, the long-term use case remained extremely robust (it would be hard to imagine Altman, arguably the world’s leading evangelist for the bright shiny future of AI, to say otherwise). In any event, financial pundits seized onto...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Data Fog Envelopes Jobs, Prices…and Tariffs

Read More From MVThis has been a week, one full of news related to politics, the economy and much else in between. But it is also a week in which absences loom large. Today is supposed to be Jobs Friday, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes its monthly report on the state of the US labor market, and we get to chew over the raw total of nonfarm payrolls created, the unemployment rate, labor force participation, number of people with part-time jobs who would rather work full time…all the fun stuff that helps us figure out where the economy is today and...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Big Tech Goes into Overdrive (Again)

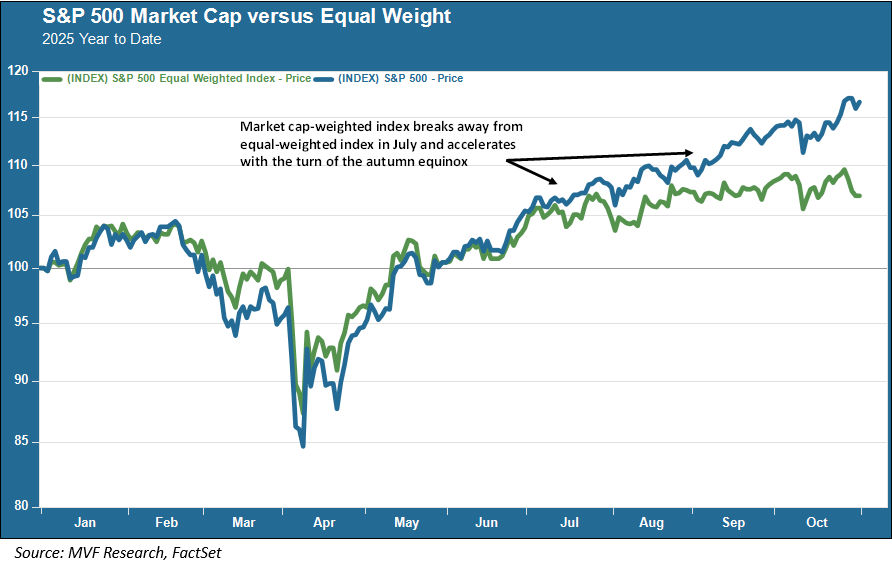

Read More From MVWell, it’s the last day of October (Happy Halloween!), and unless something really freaky and ghoulish happens between now and 4:00 pm today Eastern daylight time (don’t forget to turn the clocks back on Sunday), we will have managed yet again to avoid an October Scare, that creepy phantasm given to showing up every now and then in years otherwise unconnected – 1929, 1987, 2008 to name a few – with a bag full of tricks and no treats. This year, despite the inescapable return of bubble banter among the financial chattering class, the S&P 500 has added 2.3 percent...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Gold Hits a Speedbump

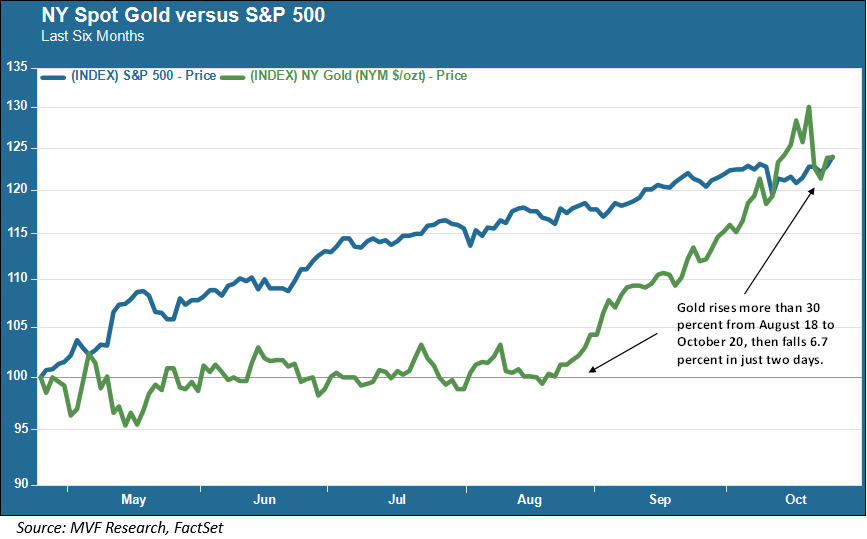

Read More From MVIt has been a strange year in so many ways, but one of this year’s odder bedfellows has been the tandem duo of US stocks and gold. These two asset classes don’t normally tango together. In 1979, gold was just about the only thing that was working for portfolios, while the S&P 500 was in the dumps and bond markets were roiled by the Volcker shock of ultra-tight monetary policy. Two decades later, 1999 was a go-go year for any stock with even the flimsiest connection to the Internet, while gold had nothing to offer other than being pretty to...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Good Bubble, Bad Bubble

Read More From MVIs it going to be one of “those” Octobers? If you tuned into pretty much any financial media this week, you would have heard “bubble” spout forth from the mouths of many a money pundit. Luminaries from JPMorgan Chase head Jamie Dimon to OpenAI maven Sam Altman have weighed in on the frothy state of the market. It’s not a hard call to make – the US stock market is undoubtedly expensive. According to Yale economist Robert Shiller’s vaunted CAPE (cyclically adjusted price to earnings) ratio, the S&P 500 is more expensive today than at any time in the history...

Read More