MV Weekly Market Flash: Hot World, Chill Markets

Read More From MVHere’s one that we’re guessing was not on your 2024 bingo card. The president of a populous and economically important Asian country decides to declare martial law, attempts to take over the media and use the military to shut down parliamentary proceedings, only to then say “just kidding” and find himself the target of impeachment by that very same parliament. All within a span of twenty-four hours. The country, of course, is South Korea and this really did happen this week, for reasons that remain shrouded in the fog of dissembling attempts at explanations by various South Korean parliamentarians and...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Market Finds Its Inner Peace

Read More From MVOn Tuesday morning this week, investors awakened to animated chatter in the financial media about tariffs, lots and lots of tariffs, aimed directly at our country’s three largest trading partners – China, Mexico and Canada. Twenty-five percent on all goods imported from the latter two, and an additional ten percent on top of the tariffs already existing with respect to China. Now, to be perfectly clear, if this proposal were to make its way from effervescent bloviating on social media to become actual policy, it would have decidedly negative consequences in the form of slower growth and higher inflation. Stagflation,...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Enduring Advantage

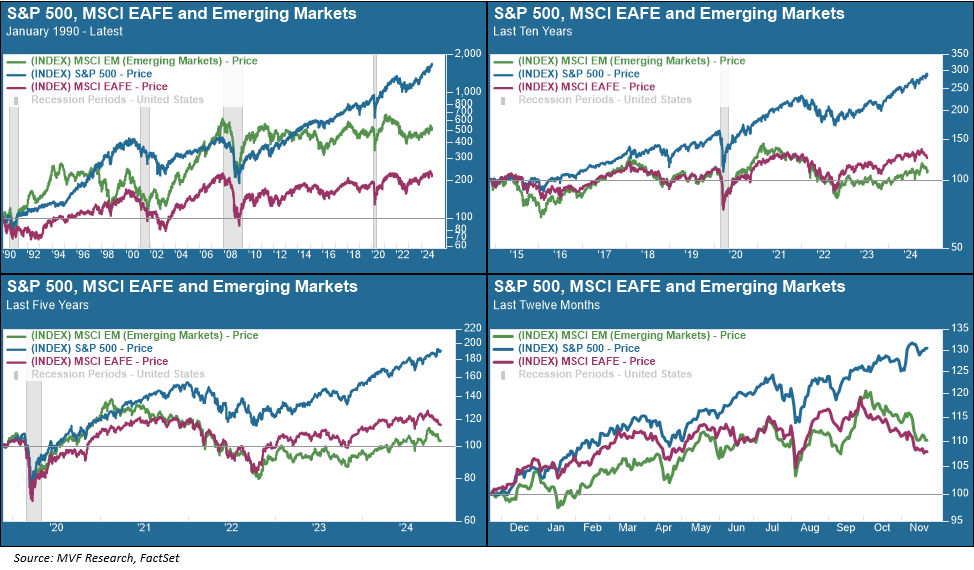

Read More From MVThere will, probably, be a time again when it will make sense to have a significant allocation of non-US equity indexes in one’s investment portfolio. But that time, in our considered opinion, is not today. As the end of the year approaches, our primary focus as always turns to our asset allocation choices for the year ahead. Some years can elapse quietly with minimal tweaks to portfolio weights, while others require extensive rethinks on a more frequent basis. We imagine that 2025 will fall into the latter category. Fair warning: our model portfolios in June may look quite different from...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The 4-3-2 Economy

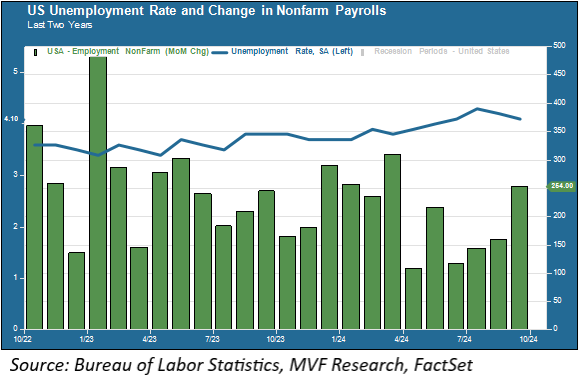

Read More From MVSo what do we know now that we didn’t know one week ago, regarding possible trajectories for the US economy? To be perfectly honest, not much. But if it is still too early to talk about the economy of the future, we can at least take stock of where we are starting from. We call it the 4-3-2 economy, which we think is a reasonable way to quantify what a soft landing looks like: Four (4) percent unemployment (the current unemployment rate is 4.1 percent). Three (3) percent real GDP growth (3.0 percent in Q2 and 2.8 percent in G3)....

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Markets Are The Guardrails

Read More From MVOur weekly market commentary has never been the space for hashing out politics, and that will not change going forward. But every now and then, politics and the economy intersect in a meaningful enough way to merit top consideration among all the topics we might cover. So it is, in the days following what is likely to be recorded in the history books of the future as one of the most consequential elections in modern American history. What does the election mean for the economy, and what opportunities and risks might be ahead in the coming year? Let’s start by...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: The Noisiest Ten Days of the Year

Read More From MVHere is what has happened, is happening and will happen between this past Tuesday, October 29, and next Thursday, November 7: the third quarter US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) report; the September Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation report – the one the Fed pays the most attention to – the September jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics; the highly consequential US election; and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting that is expected to end with another cut to the Fed funds target rate. Not to mention a bevy of quarterly earnings reports from companies including tech behemoths...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: What’s Going On With Gold

Read More From MVOver a very long history as a mainstay of the economic landscape, gold has been many things to many people. During the Second Industrial Revolution, from around the 1870s to the outbreak of the First World War, the precious metal was the sole arbiter of international monetary policy. Any nation aspiring to a place in the energetic world of global trade in those days had its currency indelibly fixed to the value of an ounce of 11/12 fine gold (that precise measurement translated into three British pounds sterling, seventeen shillings and nine pence, a unit of exchange to which everything...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: When Tailwinds Become Headwinds

Read More From MVYesterday we were participating in a panel discussion at a wealth management conference near Philadelphia, and the moderator posed an interesting question. Looking beyond the short-term environment of the next twelve months or so, he asked, what are the biggest structural concerns that keep you up at night? That’s a question that rarely gets asked at these types of events, or really anywhere in the public financial discourse, where the conversation tends to focus on the immediate, the here and now of the Fed and monthly jobs reports and quarterly earnings calls. In a world where multiple news cycles can...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: Rates Go Down, Rates Go Up

Read More From MVA lot of things have been happening in the bond market as of late. What to make of the fact that, subsequent to the Federal Open Market Committee reducing the Fed funds target rate by a larger than usual 0.5 percent on September 18, Treasury yields across maturities from six months to 30 years have gone up? The benchmark 10-year yield is more than half a percent higher than where it was one month ago. The two-year yield, which sits in closer proximity to the Fed funds rate (the overnight bank lending rate) is up a quarter percent from where...

Read MoreMV Weekly Market Flash: More Treats Than Tricks

Read More From MVIt is supposed to be the month of March that comes in like a lion, out like a lamb, according to the custodians of timeless wisdom. This year, though, that appellation could just as well apply to September. After a volatile beginning, financial markets settled down and more or less calmly navigated the twists and turns of the daily news cycles. At the end of it all, the S&P 500 posted a gain of just over two percent from the beginning to the end of the year’s ninth month – not a shabby chunk of change. So how is the...

Read More